In the last few weeks, a new virus causing pneumonia in humans has been identified: it has been temporarily called 2019-nCoV (2019 novel Coronavirus) and was detected for the first time in Wuhan, China.

The website of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) reports that by January 26th, 2020, 2026 cases have been confirmed, 1988 of them in China. Other countries involved are Taiwan, Thailand, Australia, Malaysia, Singapore, France, Japan, USA, South Korea, Vietnam, Canada, and Nepal.

All the infected patients except for one single case in Vietnam had recently traveled from China. Some patients developed severe illness, that was deadly in 56 cases (all of them in China), while others had milder symptoms that did not require long hospitalization. The symptoms of the infection with 2019-nCoV are fever, cough, myalgia and fatigue.

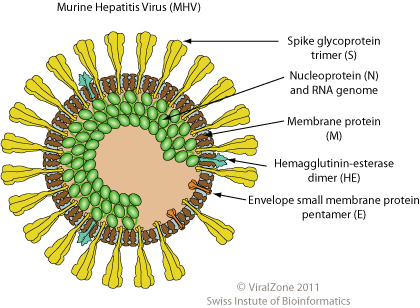

2019-nCoV belongs to the family Coronaviridae, characterised by an RNA genome with 6 or more genes, and equipped with a pericapsid (lipidic envelope in which are inserted some viral proteins). Coronaviruses usually infect mammals and birds and spread between animals of the same species, but sometimes they can be transmitted from animals to humans, such in the case of the coronavorus that caused pandemic SARS* in 2002 (transmetted by civet cats) or the one that caused MERS** in 2012 (transmetted by dromedary camels). Coronaviruses infecting humans cause respiratory diseases ranging from common cold to more severe pathologies like MERS.

The genes of Coronaviruses contain instructions for the production of the viral proteins; the most important ones are Spike (S), Membrane (M), Envelope (E), and Nucleocapsid (N).

The Spike protein sticks out of the envelope creating a crown shape visible at the microscope that gives the name to these viruses (corona is the Latin word for crown); it mediates the adhesion between the virus and the proteins on the external surface of the cells that will be infected. Sometimes S can also mediate the fusion between the infected cell and other adjacent cells facilitating the spreding of the virus.

The M protein is embedded in the membrane of the virus, causing its curvature and giving the virions a spherical shape. M interacts with the nucleocapsid that contains the RNA of the virus and the N protein.

Protein E is necessary for the formation of new particles and for their release from the infected cells, therefore it is necessary for the spread of the virus.

The new virus 2019-nCoV is thought to have originated in an animal market of Wuhan, suggesting a first transmission from an animal species to humans. Later on, however, more cases of infection in people that had not visited animal markets were reported, showing that the virus has acquired human-to-human transmission capability. Transmission of the virus is very likely to ocurr via respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes. Scientists are currently working to understand how easily the virus spreads, and to determine its virulence, that is its capability to cause illness and with what severity. At the moment, it looks like that transmission ocurrs only between close contacts.

It was initially hypothesized that snakes were the source for the new virus, but this theory was lately dismissed, and it is still unknown how 2019-nCoV originated. The sequence of its RNA is very similar to that of some bat Coronaviruses and also to the SARS virus, but investigations are ongoing to determine which animal species transmitted it to humans at the beginning of its spread.

There is currently no vaccine to prevent 2019-nCoV infection, and there is no specific antiviral treatment, but the symptoms of the disease can be treated.

The same actions to help prevent the spread of other respiratory viruses are recommended: cover your cough or sneeze, use disposable tissues, wash your hands often with soap and water or alcohol-based hand sanitizer, avoid touching your eyes, nose, and mouth with unwashed hands.

But where does a new virus come from? And how can it be transmitted between different species, spreading from animals to humans?

Emerging viruses able to infect humans have mainly RNA genomes, and they more often arise in densely populated areas with intense human activity.

Virus emergence requires several factors, such as close contacts between animals and humans, and genetic modifications of the virus. This is a three-phase process:

1) the virus acquires the capability to infect new cell types,

2) the virus adapts to the new host, and can be transmitted between individuals,

3) the new virus acquires the ability to spread epidemically through the host population.

The first two phases require genetic changes in the virus, while the third phase involves changes in the dynamic of the host population, like contacts between individuals and their circulation.

When a virus replicates, it produces lots of copies of its genetic material; viruses are not able to control the quality of the copies they produce, so they often introduce errors (mutations) in their genomes. This is how viral particles with similar but not identical genomes are produced.

Sometimes one of these errors can change the instructions for the production of the protein that binds to the surface of the host cell, and the new version of the protein may become able to bind to cells of a different species; this event is called host shift.

A viral genome can also change through other two different mechanisms called “recombination” and “rearrangement”.

Recombinations occur when fragments from genomes of similar viruses mix together, forming new sequences. That happened in the case of a Coronavirus causing bronchitis in chickens: its sequence for the Spike protein recombined with another S gene of unknown source, giving rise to a new virus able to infect turkeys causing an enteric disease; in addition, the new virus lost its capability to infect chickens.

Rearrangement occurs only when the genome of the virus is made of several fragments of DNA or RNA (segmented viruses). When two or more segmented viruses infect the same cell at the same time, their segments can be packed in the same particle, producing viruses that are a combination of the original ones.

Rearrangement can contribute to host shift as well, such in the case of the pandemic virus 2009 IAV H1N1: in 1998 fragment of influenza viruses from birds, swine and humans rearranged into a new virus circulating in swine, called H3N2 IAV; in 2009 this virus rearranged in turn with an other avian virus, producing a third virus able to spread between humans.

There is no doubt that viruses have a extraordinary capability to rapidly evolve, and are therefore particularly dangerous because they can escape host immune response and antiviral treatments. However, only a small percentage of the new viruses are able to infect a new species and to adapt to the new host. This is because the number of viral particles transmitted between individuals depends on the virus ability to grow inside the infected organism, and this is particularly tricky for most emerging viruses.

Three different scenarios are possible:

a) if the virus replicates at a low efficiency in the new host, only a few viral particles will be released (i.g by coughing or sneezing) and a very low number of new virions will reach other cells or individuals;

b) if the virus is too aggressive, the host will not survive enough to release a high number of infectious particles, and this will limit its spread (the death of the host is a disadvantage for the virus);

c) only if a virus is able to adapt quickly to the new host and to achieve a correct virus-host balance, it will be able to spread efficiently through the population.

In our modern world, the emergence of new infectious diseases and the re-emergence of others is facilitated by globalization, which allows a rapid movement of people across the planet. Travelers can carry with them new viruses to different places, enhancing their spread. Mosquitoes or other insects that convey viruses can be transferred as well, introducing pathogens into new areas. Climate change has also a role in this context, for example when a vector finds favorable climate conditions for its growth and reproduction in other areas, contributing to the diffusion of the associated viruses.

Nonetheless, globalization also offers us some advantages to counteract the emergence of new viruses, such as the rapid communication and collaboration between scientists all over the world. This is what is happening for 2019-nCoV: a few days after the first reported cases of infection, the virus was identified and sequenced, and the data were shared allowing several groups of researchers to start working to identify the source of the virus, to develop diagnostic methods as well as mathematical models to predict its transmission rate.

Researchers from different countries are currently working to understand the mechanisms by which 2019-nCoV is causing pneumonia and to limit its transmissibility.

*SARS Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome; ** MERS Middle East Respiratory Syndrome

To learn more about the general features of viruses, read my post The fantastic world of viruses.

Bibliography

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical-distribution-2019-ncov-cases

World Health Organization: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019; https://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ ; https://www.who.int/csr/sars/en/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/summary.html

Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Huang C. et al, Lancet 2020, http://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30183-5

Coronaviruses: genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. Chen Y. et al., J Med Virol 2020, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0

Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Schoeman D., Fielding B.C., Virol J 2019, http://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0

Evolutionary ecology of virus emergence. Dennehy J.J., Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci 2017, http://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13304

Emerging and re-emerging viruses in the era of globalisation. Zappa A. et al., Blood Transfus. 2009, http://doi.org/10.2450/2009.0076-08

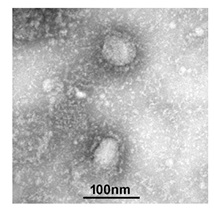

Photo from http://www.im.cas.cn/xwzx2018/jqyw/202001/t20200124_5494401.html

Puedes encontrar este articulo traducido al Castellano en https://www.dciencia.es/el-nuevo-coronavirus-2019-ncov-como-nace-un-virus/

LikeLike