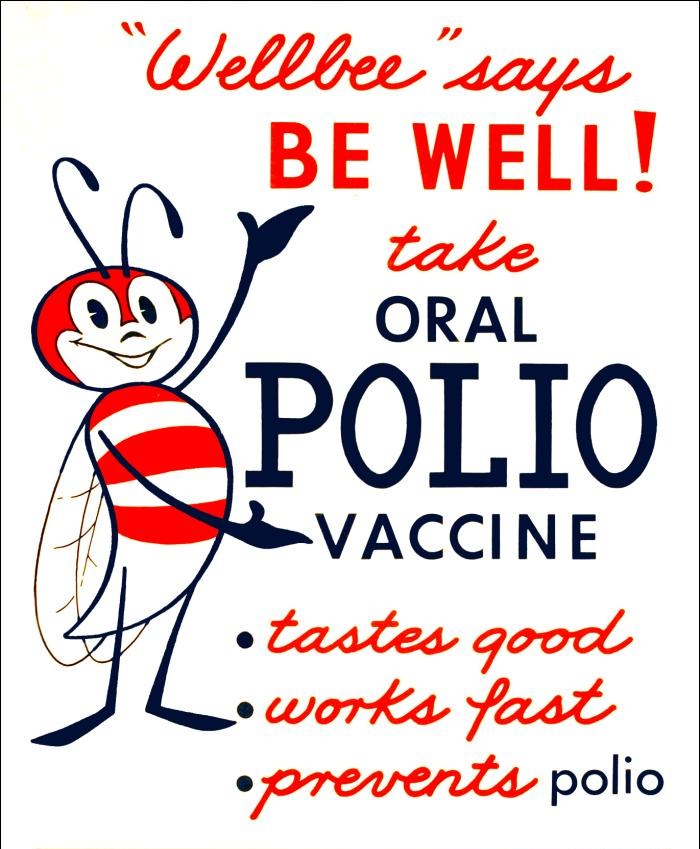

1963 CDC polio vaccine poster

Fom CDC Public Health Image Library, #7224 (Public Domain)

We have started 2020 struggling with an emerging virus: we have changed our lifestyle trying to limit its diffusion, and we are aware more than ever in our lifetime of the threat of viruses and infectious diseases in general. Most of us are looking forward to a vaccine, and are wondering when it will be available.

Infections can cause death

Infectious diseases have shaped the history of humankind: outstanding examples are the Black Death of 1347-1350 which killed one-third of the world population, and the so-called Spanish flu which killed 100 million people in 1918 reducing the European population to half.

Besides these extraordinary examples, there are many other deadly infectious diseases like measles, diphtheria, and polio. These infections no longer cause the enormous number of deaths thanks to the availability of vaccines, but we must not forget their dangerousness. Measles, for example, used to cause an average of 2.6 million deaths worldwide every year before the introduction of vaccination in 1936, while in 2018 the number of victims was 140.000 globally.

Who invented vaccination?

Vaccination was invented by Edward Jenner in 1796.

In the XVIII century, smallpox was very common in Europe, killing 400.000 people every year. It was known that those who survived smallpox became immune to a second infection and that dairymaids exposed to cowpox by touching lesions of infected cows were resistant to smallpox. Jenner thought that cowpox could be deliberately transmitted among humans to prevent smallpox infection. To test his hypothesis, he collected fresh material from a lesion in the hand of a dairymaid with cowpox, and he transferred it into a small incision in the skin of an 8-year-old boy (James Phipps). The boy immediately developed a fever and discomfort, but the symptoms lasted only a few days. Two months later, Jenner transferred in the skin of the boy material collected from a person with smallpox: James did not develop the disease and Jenner concluded that his method was successful!

In 1797 Jenner sent a manuscript with the description of his experiment to the Royal Society, but but he did not receive the consideration he deserved, and the article was not published. One year later Jenner published a booklet including more cases and observation (“An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, a disease discovered in some of the western counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire and Known by the Name of Cow Pox”) sharing his knowledge with the other scientists.

Since the material used by Jenner came from the cow, vacca in Latin, and the scientific name of cowpox was Vaccininia, his technique was later called vaccination.

Vaccination spread worldwide, and Jenner’s vaccine led to the elimination of the smallpox virus in 1980 when WHO declared its eradication. Variola virus, the causative agent of smallpox was eradicated. If it were an animal we would say that it became extinct; this happened because most of the population was immune and there were not enough susceptible individuals for the virus to infect them and spread.

What is inside a vaccine?*

Existing vaccines contain one of these components:

- Attenuated (weakened) microorganisms that have been made no longer able to cause the disease (no longer pathogenic)

- Inactivated (killed) microorganisms through exposure to heat or chemicals

- Proteins or subunits of proteins of the microorganism (subunit vaccines)

- Toxoids: toxins produced by the microorganism modified in the lab to be harmless

How do vaccines work?

When vaccines are injected, their components attract cells of the immune system at the site of injection causing a localized inflammation. These cells are called antigen-presenting cells (APCs). APCs internalise the substances that constitute the vaccine and transport them to the lymph nodes, where they “present” those substances (antigens) to other cells of the immune system: T cells. All the T cells that can recognize those specific antigens start proliferating and interact with the B cells, which in turn, need to specifically recognize the same antigens to start multiplying. All the B cells selected through these mechanisms exit the lymph nodes and circulate in the blood, producing antibodies.

This first phase when antigens are recognised and presented is shared between natural infection and vaccination, with the only difference being that vaccination is not followed by the disease.

The T cells will kill the infected cells (and with them the microorganism responsible for the disease), and the B cells will produce a huge amount of antibodies that will attack the pathogen contributing to its elimination.

How long does the effect of vaccination last?

After this phase, most of the B and T cells that had proliferated are eliminated by our organism, but some of them survive and become memory cells. They are sentries ready to recognise and quickly attack the same pathogen if it happens to invade our organism a second time. Moreover, the antibodies already produced remain in the blood for a variable amount of time.

This is how we become immune to a disease: we have antibodies made in advance, and B and T cells ready to eliminate a pathogen during the first steps of the infection. We will not even notice that all this is happening, or, if anything, the pathogen will merely induce mild symptoms.

Why is vaccination important?

Since Jenner’s vaccine, many advances have been made: Louis Pasteur demonstrated that germs cause diseases, the mechanisms of immunity were discovered and many other vaccines were developed, reducing infant mortality, improving general health conditions and increasing life expectancy. Vaccines are considered among the most important advances in public health together with water potabilisation and antibiotics.

What is herd immunity?

Vaccination is an individual protection, but it can also protect the rest of the population by limiting the spread of the pathogen; this is the so-called herd immunity, but for it to happen the majority of the population must be immunized through vaccination (75-95% depending on the pathogen). Ideally, all healthy individuals should get vaccinated to protect by herd immunity those who cannot be vaccinated, those whose immune system does not work properly (immunocompromised) or the newborns that have not been vaccinated yet.

The newest vaccines*

Current technologies allow the study of infectious diseases and to design more sophisticated vaccines. On one hand, we can sequence the genome of viruses and bacteria and to use informatics tools to predict which proteins and which portions of them (epitopes) are more likely to be efficiently recognized by the immune cells (Reverse Vaccinology). On the other hand, we can sequence B cells from patients that already had the disease and identify which among all the different antibodies that the organism had produced are the more effective to intercept the microorganism (Reverse Vaccinology 2.0). Scientists are also exploring new types of vaccines containing fragments of DNA and RNA of the microorganism to obtain better vaccines.

Useful definitions

Immunity: protection against an infectious disease; those who are immune against a pathogen can be exposed to them without developing the disease.

Immunisation: The process by which a person or animal becomes protected against a disease.

Vaccination: introduction in an individual of material designed to induce an immune response that will protect against a specific infectious agent.

Vaccine: product able to stimulate the immune system to give immunity against a specific infectious agent and protect against the disease.

Plasma cells: B cells that produce huge amounts of antibodies.

Antibodies: proteins produced by the immune system, capable of specifically recognising microorganisms during an infection.

*Author’s note: This post was written and published in April 2020, during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the end of 2020, mRNA or vector-based anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccines became available. The mechanism of action of these vaccines is the topic of two other posts in this blog: https://virusandco.art.blog/2020/11/23/the-moderna-and-pfizer-vaccines-promising-results-in-less-than-one-year-since-the-beginning-of-the-pandemic/ and https://virusandco.art.blog/2021/01/13/the-oxford-astra-zeneca-vaccine-a-viral-vector-based-vaccine/

BIBLIOGRAPHY

World Health Organization: https://www.who.int/topics/vaccines/en/ ; https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles ; https://www.who.int/csr/disease/smallpox/en/

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/immunisation-vaccines/facts/vaccine-preventable-diseases

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/vaccines-list.html ; https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vac-gen/imz-basics.htmTranscript of Jenner’s original pubblication: https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/cphl/history/articles/jenner.htm

Chapter three: Introduction to Vaccines and Vaccination; Micro and Nanotechnologies in Vaccine Development , Depelsanaire A.C.I. et al, pag. 47-62, Elsevier, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-39981-4.00003-8

Vaccine evolution and its application to fight modern threats, Andreano E. et al., Frontiers in Immunology, 2019 https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01722

Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination, Riedel S., Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent), 2005, https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2005.11928028

Understanding modern-day vaccines: what you need to know, Vetter V. et al., Annals of Medicine, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2017.1407035

2 thoughts on “Vaccines, antibodies and herd immunity (in a nutshell)”