The goal of gene therapy is to cure monofactorial genetic disorders, caused by mutations in a single gene.

In the sequence of each gene are the instructions for the production of a protein, and every block of three bases (codon) corresponds to a specific amino acid. Alterations in the DNA sequence (mutations) affect the sequence of amino acids in the protein and on its function.

Even mutations on a single base may have devastating consequences on the final protein. For example, the substitution of a base with a different one can change the amino acid coded by that codon (missense mutation), while the insertion or loss (deletion) of one base shifts the way the sequence is read, causing the translation of a completely different protein (frameshift mutation).

Sometimes, the substitution of a base transforms the original codon in a stop codon, a signal that indicates the end of the protein (nonsense mutation), this type of mutation causes the early interruption of the amino acid sequence and the production of a shortened and non-functional protein.

Occasionally, after the substitution of a base, another codon that encodes for the same amino acid is obtained; these mutations do not affect the amino acidic sequence of the protein and are called silent mutations.

The result of the mutation in a gene that impedes a protein to carry on its function properly is a disease. To undo the effects of mutation on a single protein, we can provide the cells with the correct copy of its gene.

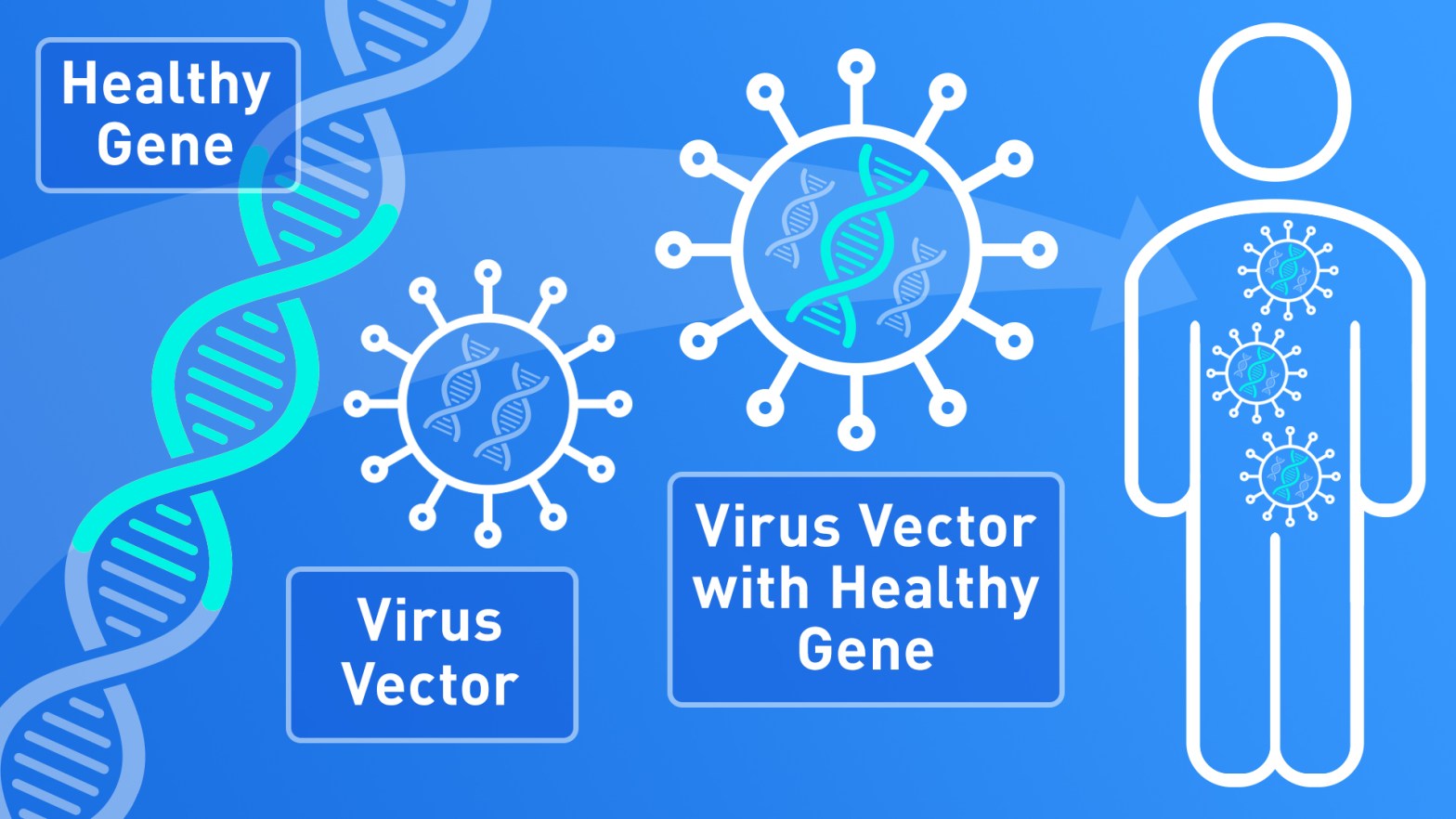

To deliver a DNA fragment to our target cells, we need a vector to convey it. Often, virus-derived vectors are used, to take advantage of their natural ability to enter into cells and release genetic material.

The type of viral vector is chosen according to its capacity to infect the cell type that needs to receive the correct copy of the gene (therapeutic gene). Remember that every single cell of an organism contains all the DNA, but only part of it is actually used: this makes a muscle cell different from a neuron or a kidney cell, for example.

The most relevant viruses for gene therapy are the lentiviruses, retroviruses, adenoviruses, and adeno-associated viruses.

Viruses are modified (engineered) to remove their pathogenic features, and their genes are replaced bu the therapeutic gene and other DNA sequences needed for its correct expression.

The gene therapy product can be administered directly to the patient (in vivo), or the treatment can be performed on cells (ex vivo) that will be later transferred into the patient (cellular gene therapy).

When the viral vectors enter into the target cell, it releases the therapeutic DNA that will be transcribed and translated to produce the missing protein. In most cases it is not possible to reach every single cell that needs it, however, the treatment is considered successful it the correct protein is produced in a sufficient amount to reduce the symptoms of the disease and improve the patients’ quality of life.

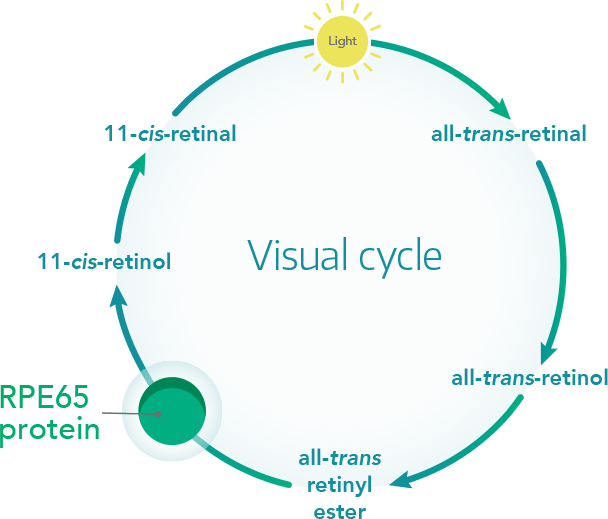

In 2018, the gene therapy product Luxturna™ (AAV2-hRPE65v2) was approved both in Europe and the United States to cure a form of progressive inherited blindness called retinal dystrophy, caused by a mutation in the RPE65 gene. Protein RPE65 takes part in the visual cycle, and it is necessary to transform light stimuli that reach the eye into electrical signals sent to the brain for image elaboration. When light reaches the eye, a molecule called 11-cis-retinal (a photosensitive form of Vitamin A) is transformed in all-trans-retinal; such conversion triggers a cascade of chemical reactions that generate the electrical signal.

All-trans-retinal, however, is not photosensitive, so it must be reverted to 11-cis-retinal by RPE65 to transform new light stimuli into electrical signals.

(For example, when your eyes are hit by a car light in the night you need a few seconds before being able to see again because a huge amount of light reached your eyes and RPE65 need times to reconvert a big number of All-trans-retinal molecules into 11-cis-retinal again).

In the case of di Luxturna™, a correct copy of RPE65 is conveyed by a vector derived from an adeno-associated virus (AVV2) with a high affinity for human photoreceptor cells. The virus is injected only once in the back of the eye (in vivo), enters the cell of the retinal pigment epithelium, and releases the DNA to be used by the cells to produce functional RPE65 proteins.

Promising results have been obtained also for the gene therapy of β-thalassemia.

is a disease due to mutations in the gene for β-globin, causing a reduction or absence of Haemoglobin, the protein used by the red blood cells to transport oxygen. Patients affected with this disease need frequent blood transfusions during their entire life.

In 2017 a clinical trial for β-thalassemia treatment by cellular gene therapy was launched, including both adult and pediatric patients. Blood cells were collected from the patients and infected ex vivo with a lentivirus-derived vector carrying the β-globin gene. After the treatment, the cells were transferred back to the bone marrow of the same patients.

This therapy has reduced the frequency of blood transfusion in 6 out of 7 patients, who have become able to produce a sufficient amount of haemoglobin for a long time.

Several other preclinical and clinical studies for the gene therapy of many other inherited diseases are currently ongoing.

Leave a comment if you want to know more about gene therapy or viral vectors!

FDA infographic by Michael J. Ermarth

Bibliography:

List of gene therapy products approved in the USA: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/approved-cellular-and-gene-therapy-products

Definition of gene therapy and other useful terms:

https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/what-gene-therapy-how-does-it-work

https://www.esgct.eu/Useful-Information/Gene-and-cell-therapy-glossary.aspx

https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/therapy/procedures

https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/therapy/genetherapy

Timeline of gene therapy:

https://www.telethon.it/en/what-we-do/terapie-e-diagnosi/terapie-avanzate/gene-therapy

https://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/genetherapy/success/

Luxturna™:

https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/luxturna

https://luxturnahcp.com/how-LUXTURNA-works/mechanism-of-action/

Gene therapy for β-thalassemia:

Intrabone hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy for adult and pediatric patients affected by transfusion-dependent ß-thalassemia, Marktel S. et al., Nature Medicine 2019, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0301-6

2 thoughts on “When viruses are the ally: successful gene therapy for retinal dystrophy and beta-thalassemia”