Last week I attended the British Society for Immunology Congress in lovely Edinburgh.

At last a “real” in-person congress (the online option was also available) with real interactions with other scientists from all over the United Kingdom and some international guests.

When I take part in big congresses like this, with parallel sessions on different topics, I make time to attend some of the sessions not strictly related to my research, to learn something new.

This time, I have particularly enjoyed the session about the biological clock of the immune system. It looks like that the immune cells migrate from the blood to the lymph nodes during the evening, to present the antigens they have encountered during the day to other immune cells. This means that there is an ideal time of the day to get a vaccine or any other therapy that affects the immune system.

Also, the time at which an organism eats, and therefore activates certain mechanisms in its metabolism, has an effect on the activity of the immune system, and the type of diet can alter the composition of the bacteria that live in our gut (intestinal flora or microbiota), which in turn can modify the levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory signals in our blood and tissues.

Another fascinating fact is that current or previous infections can modify the outcome of an infection by a completely different microorganism. For example, did you know that the presence of a parasite in the intestine (Heligmosomoides polygyrus) can promote the production of a certain type of white cells in the bone marrow, and help the immune response against the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) that infects the lungs? Or that malaria (caused by the parasite Plasmodium falciparum living in red blood cells or liver cells depending on the phase of its development) can cause an imbalance in the intestinal flora, increasing the risk for children of being infected by Salmonella bacteria?

What’s more, it seems that during the Spanish flu pandemic (mentioned here), most of the deaths were caused by a bacterium (Streptococcus pneumoniae) that took advantage of the organisms already weakened by the viral infection to further damage the lungs, and not to the virus itself. And recently, it has been discovered that a previous infection by bacterium Klebsiella pneumoniae can limit the activation of the immune cells called Natural Killer cells, making a later influenza virus infection less dangerous, since Natural Killer cells are partly responsible for lung damage in an excessive immune response.

In other words, I am more than ever in awe of the complexity of the immune system and of the many mechanisms through which it interacts with pretty much all processes happening in our body!

In addition, in the last part of the congress, Professor Paul Moss from the University of Birmingham and Professor Dame Sarah Gilbert from the University of Oxford went through all the discoveries and progresses made by the scientific community during the last two years: from the first reported cases of atypical pneumonia to the administration of the COVID-19 booster jab. I think that nobody, including the most expert immunologist, was so optimistic at the beginning of the pandemic to anticipate so many important results in such a short time!

And it was thanks to the amazing effort and collaborations between scientists all over the world, that we were able to enjoy those four intense days about Immunology and to visit the charming city of Edinburgh (with a COVID pass and the mask on, of course!)

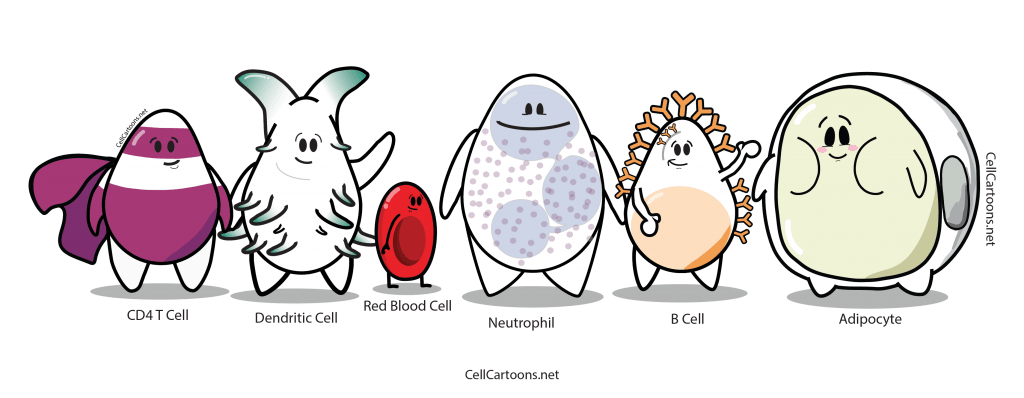

Image from cellcartoons.net under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND licence.