When we talk about human papillomavirus (HPV) we are actually referring to more than 200 different viruses, all belonging to the Papillomaviridae family, classified into five genera (α, β, γ, μ, ν).

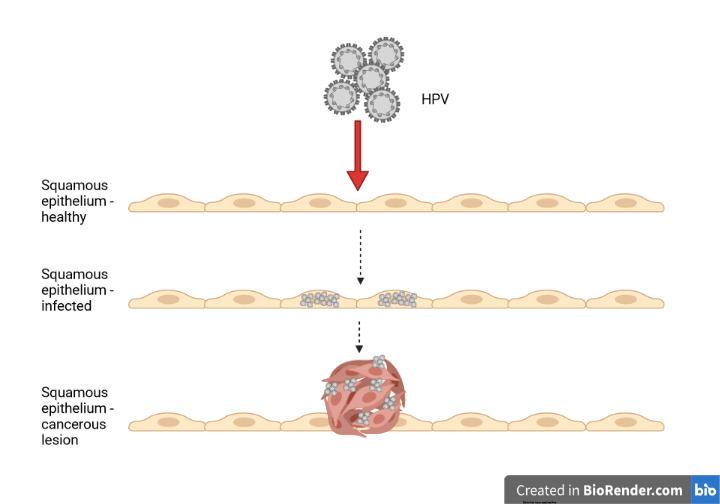

They are DNA viruses that infect the skin or the mucosae and are divided into low-risk and high-risk types, depending on their ability to cause cancer. It is estimated that 4 out of 5 of us will be infected by an HPV at least once during our life, most of us without even realising it. In fact, in most cases papillomavirus infections are asymptomatic.

In general, HPV infections do not cause cell death, and the virus never spreads to the bloodstream.

In the case of low-risk papillomaviruses, the infection can manifest with the growth of warts on the skin or papillomas on the mucosae, because the virus induces the proliferation of epithelial cells that in turn produce a thick layer of keratine.

High-risk papillomaviruses (there exist at least 15 of them) can cause more severe lesions, that, if not treated, can evolve into tumours caused by the persistent presence of the virus. Such tumours can affect tissues in the upper respiratory tract and both male and female genitals.

Harald zur Hausen was the first to demonstrate the role of HPV in carcinogenesis, receiving the Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine in 2008.

Benign lesions caused by low-risk viruses heal spontaneously since the immune system is able to eliminate the virus without any medical treatment. However, sometimes, the cells responsible to start the immune response fail in their activity, and, as a result, the immune system grows tolerant to the virus.

In addition, HPVs have evolved different ways to evade the immune system:

- They do not produce high quantities of viral antigen

- do not kill the infected cells

- inhibit the production of inflammatory signals

- limit the presentation of viral proteins on the surface of the infected cells.

With these viral strategies in place, the immune system is not alerted of the presence of the virus, and the infection can go on unnoticed. This gives time to the oncogenes (tumour-inducing genes) to modify the infected cells and induce their cancerous transformation, for example inducing the fusion of neighbouring cells, or blocking the last phase of cell division preventing the two daughter cells to separate. Simply put, the virus takes the control of the infected cells and alters their cycle and metabolism.

At least 40 types of HPV infect genitals, and high-risk HPV-16 and HPV-18 alone cause 70% of all cervical cancer cases.

The uterine cervix is the lower portion of the uterus, and it can be divided into two parts (exocervix and endocervix) covered by two different cell types: epithelial squamous cells, and glandular cells. Depending on the cell type affected by the infection, two different types of tumour can develop, called squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, respectively.

HPV infection of the cervix can be diagnosed through the Pap-test, the sampling of cells from the cervix to identify the presence of tumoural cells, or with the HPV-test, which determines the presence of viral DNA. Early diagnosis is essential to stop the development of cancerous lesions.

Thanks to the development and administration of prophylactic vaccines against some HPV types, cervical cancer is now the fourth most common cancer among women, after being the second one for a long time: however, it still causes 6,5% of all tumours diagnosed in the world female population.

HPV, particularly HPV-16, can also cause oropharyngeal squamous carcinoma, with the same mechanisms as cervical cancer: if the immune system fails to eliminate the virus early enough, the infection becomes persistent and the virus induces the tumoral transformation of cells. Similar tumours are also caused by exposure to smoke and alcohol independently of HPV (HPV-negative), but, recently, the proportion of HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas has increased and HPV is bound to become its main cause.

HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas are more frequent in men than women.

There are three approved vaccines against HPV, all based on the viral protein L1: many units of L1 assemble to form virus-like particles lacking viral DNA and all other viral proteins, and therefore not infectious and not oncogenic. The immune system recognises the virus-like particles and produced antibodies against L1, including neutralising antibodies able to block the virus and prevent infection.

The first vaccine, authorised in 2006, contains L1 proteins of the most common low-risk and high-risk HPVs (HPV-6 and HPV-11; HPV-16 and HPV-18, respectively). In 2009 a second vaccine was approved, exclusively directed against HPV-16 and HPV-18. More recently, in 2014, a third vaccine was approved, directed against 9 different types of HPV (HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-16, HPV-18, HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-45, HPV-52, and HPV-58).

These vaccines have proven safe and effective, preventing more than 90% of infections; unfortunately, their administration in low-income countries is still limited, due to the high production and transportation costs.

Do not forget that HPV infection affects both sexes, therefore, to reduce the viral spread and to decrease the incidence of HPV-caused tumours (not only cervical cancer), both men and women are eligible to receive the vaccine.

Image created in BioRender.com by Carla Usai

Bibliography

European Centre for disease prevention and Control https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/human-papillomavirus

An update on Human Papilloma Virus vaccines: history, types, protection and efficacy, Yousefi Z et al., Frontiers in Immunology 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.805695

International standardization and classification of human papillomavirus types, Bzhalava et al, Virology 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2014.12.028

Epidemiology of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer, Pytynia KB et al., Oral Oncology 2014, https://10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.12.019

Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries, Sung H et al., CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2021, https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660

Associazione Italiano Ricerca sul Cancro https://www.airc.it/cancro/informazioni-tumori/guida-ai-tumori/tumore-alla-cervice-uterina

Istituto Humanitas https://www.humanitas.it/malattie/infezione-da-hpv-papilloma-virus/