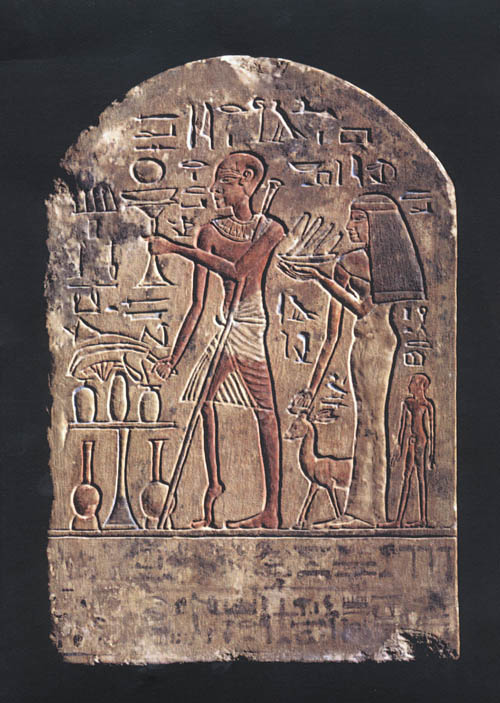

Photo: Stele depecting a man probably affect by polio, Egypt, XVIII dinasty, by Fixi, available under lincence: CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The news of poliomyelitis (polio) cases among children in Gaza came as a bit of a surprise to me, as I (wrongly) thought polio had been eradicated.

Unfortunately, while polio is not as common as in the past, the virus is still circulating in the population.

Let’s see what polio is, how it spread, when and where it has disappeared, and why it is back.

What is poliomyelitis and how is it transmitted?

Poliomyelitis (a.k.a polio) is a highly contagious viral disease mainly affecting children under the age of 5. The virus that causes polio can be transmitted person-to-person via the oral-fecal and respiratory routes, through contaminated food and water.

Since an infected person is contagious even before the onset of specific symptoms, limiting the spread of the virus in the initial phase of an outbreak can be difficult.

The early symptoms of polio are fever, weakness, headache, and vomiting, followed by stiffness of the neck and arms. In 1 out of 100 cases, polio causes flaccid paralysis (usually of the legs) with a 50% probability of being irreversible. The most severe form of polio, bulbar poliomyelitis, is characterised by the paralysis of the muscles needed for breathing, swallowing, and speaking. Five to 10% of paralysed polio patients die because of the paralysis of their respiratory muscles.

About half of the people who had acute paralysis (not permanent) because of polio, end up suffering from post-polio syndrome (PPS), characterised by the worsening or the new onset of neuromuscular symptoms, even decades after the infection. Experimental studies have shown that the virus can persist in the nervous cells of mice, and this might be one of the causes of PPS.

Poliomyelitis cannot be cured, but it can be prevented with vaccination.

The Poliovirus

Poliomyelitis is caused by Poliovirus (PV), one of the best-known and characterised viruses so far. Even if Poliovirus was formally described in 1890, poliomyelitis was already known in ancient times, as suggested by an Egyptian stele depicting a man with a deformity compatible with polio.

PV has a diameter of 30 nm (a thousandth of a millimetre) and an RNA genome; it belongs to the Picornaviridae family and Enterovirus genus. There are three wild-type serotypes of PV (WPV1, WPV2, and WPV3) that use the same receptor to invade human cells.The incubation lasts 5 to 25 days.

PV can infect very few animal species, and humans are the only reservoir allowing its replication and transmission. Poliovirus replicates in the lymphoid tissues of the pharynx and the intestine (tonsils and Peyer’s patches), then migrates to the lymph nodes and the blood. Sometimes Poliovirus invades the central nervous system (CNS) destroying the motoneurons and causing paralysis, the hallmark of poliomyelitis.

The polio vaccines: IPV and OPV

There are two polio vaccines: the injectable inactivated vaccine (IPV, or Salk vaccine) and the oral attenuated vaccine (OPV, or Sabin vaccine), both available since the 1950s.

IPV contains inactivated versions of the three serotypes. This vaccine induces antibody production in the blood, therefore protecting from the disease, but it does not induce enough antibodies in the intestine and is not effective in avoiding virus replication and transmission. OPV containes attenuated viruses (mutated, do not cause disease), and induces the same immune response as the wild-type virus, characterised by the production of antibodies both in the blood and the intestine. OPV is available as a trivalent vaccine (including all serotypes), bivalent (including two serotypes), or monovalent (against only one serotype) and can be customised according to the strains circulating where it is administered. As opposed to IPV, OPV reduces viral shedding through the faeces and therefore limits its transmission.

The eradication plan

In 1988, the World Health Organisation (WHO) launched a global eradication plan (Global Polio Eradication Initiative, GPEI); at the time, the virus was endemic in all continents, causing about 1000 new paralysis and 50-100 deaths every day.

The GPEI has reduced polio incidence by 99% worldwide, and the eradication of two out of three wild-type serotypes:

- WPV2 eradication was declared in 2015 (last reported case in 1993, India)

- WPV3 eradication was declared in 2019 (last reported case in 2012, Nigeria)

- WPV1 is still endemic in Afghanistan and Pakistan (WHO data, October 2023).

Both OPV and IPV have been instrumental in reducing polio global incidence. The use of IPV, combined with high hygiene standards, allowed polio eradication in several countries in Northern Europe. However, silent transmission of Poliovirus is still possible in areas where IPV was the only vaccine used.

Sometimes, the attenuated virus in OPV can mutate during its replication in the intestine and evolve into disease-causing strains called vaccine-derived Poliovirus (VDPV). These strains circulate in low immunisation areas and can start new outbreaks.

Eradication plans work only when they are fully implemented worldwide. This means that, as long as there are areas of endemic transmission, the Poliovirus is not eradicated, and failure to control its spreading constitutes a global threat. Vaccinated individuals can be infected by the virus without developing the disease (health carriers) and contribute to the transmission chain.

Why is polio back in Gaza?

Despite the global eradication plan that ensured vaccination coverage worldwide, Poliovirus is still circulating silently.

In areas where adequate hygiene is not possible, where clean water is not available and the population is weakened by famine, as it happens in war zones, the virus can easily spread, replicate, and cause the disease in unvaccinated children.

Poliovirus was found in water samples from Gaza in July 2024, at the same time when three children were showing signs of flaccid paralysis. This is why WHO and UNICEF organised a vaccination campaign in the Gaza Strip for 640,000 children below the age of 10. It is estimated that a vaccination coverage of 95% can an epidemic in the area.

The history of polio highlights that viruses must be kept under control. Science provides potent tools for eradication, but if there are even very few carriers of the virus, it can spread again under proper conditions and cause diseases that we thought belonged to the past.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

World Health Organisation (WHO), Poliomyelitis fact sheet (Oct 2023) https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/poliomyelitis

Viralzone: Picornaviridae https://viralzone.expasy.org/33

Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS), Poliomielite (Nov 2019) [Italian only] https://www.epicentro.iss.it/polio/

GPEI – Global Polio Eradication Initiative https://polioeradication.org

The Fight against Poliovirus Is Not Over, Mbani CJ et al., Microorganisms 2023 https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11051323

Poliomyelitis, Henry R, Emerging Infectious Diseases 2019 https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2508.ET2508

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC): Disease factsheet about poliomyelitis (Novembre 2023) https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/poliomyelitis/facts

World Health Organisation (WHO) News: Humanitarian pauses vital for critical polio vaccination campaign in the Gaza Strip (16/08/2024) https://www.who.int/news/item/16-08-2024-humanitarian-pauses-vital-for-critical-polio-vaccination-campaign-in-the-gaza-strip