Hepatitis is now a hot topic, due to the recent severe cases of liver inflammation in children between 1 month and 16 years of age in different countries. The first (and more numerous) cases have been reported in the United Kingdom, but also in Italy, Spain, Romania, United States, Israel, and other EU countries.

The cause of this acute paediatric hepatitis, that in some cases had lead to liver transplantation, is still unknown; moreover, it is not clear whether a real outbreak is taking place, or if the recent events had rase the awareness on this condition (when we actively look for something, we are more likely to find it). While some hypotheses are under study, including the involvement of adenovirus infection (all correlations with SARS-CoV-2 or with the COVI-19 vaccine have been discarded), the advice is to rely on respiratory and hand hygiene and to pay attention to symptoms such as fever, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, fatigue, dark urine, light-coloured stools, and jaundice (yellow discolouration of skin and eyes).

Hepatitis can be caused by viruses (as I mentioned here), by toxic substances (alcohol, excessive amounts of some drugs, fungal toxins, etc) or can be a symptom of autoimmune diseases (misdirected reactions of the immune system against some components of the human body).

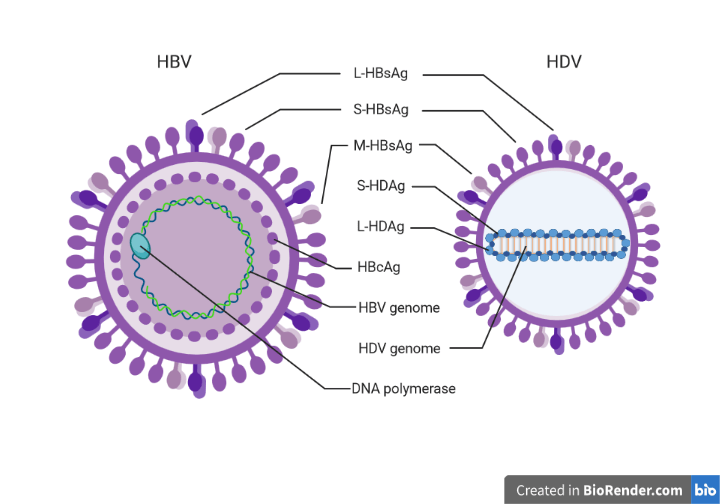

Viral hepatitis is a very common disease, but often under-diagnosed and, as a consequence, not treated. This is particularly true in the case of hepatitis delta, caused by the combination of two viruses: hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis delta virus (HDV). In some cases both viruses infect a person at the same time (co-infection), while in others, a patient already infected by HBV can be later infected by HDV (super-infection). HBV-HDV double infection causes the most severe form of viral hepatitis that, if not treated, can lead to very severe consequences, including liver cancer. It is estimated that about 300 million people in the world are infected by HBV, and that 4,5% of them have been in contact with HDV, but real numbers might be even higher.

For both HBV and HDV transmission occurs through infected blood or other body fluids, or, especially in the areas where they are endemic, from mother to child at birth or early childhood.

Hepatitis delta virus, which I studied for 7 years, is a very interesting virus, with very peculiar characteristics:

- It is the smallest virus known to infect humans

- It has a RNA genome

- Its replication occurs through mechanisms not seen in other human viruses

- It shares similarities with some plant viruses (viroids)

- It has only two proteins (L-HDAg, S-HDAg), therefore depends almost entirely on human proteins

- It can produce new viral particles and infect other cells, only in the presence of HBV

- Its external layer (envelope) is made of HBV surface proteins.

This last characteristic has turned out to be very useful to limit the spread of the infection since the vaccine against HBV is highly protective also against HDV. If you, like me, were born in the 80s in Italy, you may remember receiving your HBV vaccination in the 90s, when it become compulsory. The HBV vaccination campaign was very successful and contributed to a strong reduction of the cases of hepatitis delta in Italy, where HDV was endemic and is now considered soon to be eradicated.

However, it is estimated that about 12 million people worldwide are currently infected with HDV, because in many areas vaccine coverage is still low; the number of people living with this virus can be even higher, since in many cases HDV diagnostic tests are not performed. (In the documentation about the recent cases of acute paediatric hepatitis, I have often read that the patients were negative for HBV, HCV, HAV, HEV, “and HDV if the test was available”).

Since HDV produces only two viral proteins, it relies on human proteins from the infected cells to replicate, therefore the development of specific antivirals has proven quite difficult (to block viral replication, we should block cellular proteins, with potentially severe side effects), and, unfortunately, the treatments commonly used against HBV are not effective against HDV.

New antivirals have recently been developed with different mechanisms of action to inhibit various steps of HDV infection, and some of them are giving promising results in clinical trials. In particular, two new drugs blocking respectively HBV and HDV viral entry in liver cells and blocking the formation of new HDV infectious particles have been conditionally approved in the United States and the European Union (approved before the end of clinical trials, because benefits are clearly largely overcome risks)

Despite HDV being discovered 45 years ago (in 1977 in Italy by Prof. Mario Rizzetto), there are still many things we do not know about how it causes the disease, and, most importantly, we still do not have a specific cure. Since HDV is more common in economically less developed countries, hepatitis delta have been for many years a neglected disease.

The conditional approval of the new drugs is a first step towards the improvement of the quality of life of patients with hepatitis delta, but more is needed: research must continue to fully understand what happens in the liver of infected patients, awareness about this disease needs to be raised to encourage prevention through vaccination and discourage high risk behaviours, and more resources are needed to ensure diagnosis in all suspected cases and improve vaccination coverage in developing countries.

Image created in BioRender.com by Carla Usai (L-HDAg, S-HDAg: HDV proteins; S-HBsAG, M-HBsAg, L-HBsAg: HBVsurface proteins; HBcAg: HBV core protein). Figure not drawn to scale

Bibliography:

Review article: emerging insights into the immunopathology, clinical and therapeutic aspects of hepatitis delta virus, Usai C et al., Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2022 https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.16807

World Health Organisation page about acute severe hepatitis in children https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/multi-country-acute-severe-hepatitis-of-unknown-origin-in-children