I test sierologici determinano la presenza nel siero (ovvero la parte liquida del sangue che rimane dopo la coagulazione) di specifiche proteine.

Nel caso dei test sierologici per COVID-19 si ricercano nel siero gli anticorpi anti-SARS-CoV-2 (anche gli anticorpi sono proteine).

L’organismo umano produce 5 tipi di anticorpi diversi (IgA, IgD, IgE, IgG e IgM, dove “Ig” sta per immunoglobuline, sinonimo di anticorpi), ma nel caso dell’infezione da SARS-CoV-2 solo IgG e IgM sono di interesse.

Le IgM vengono prodotte nelle fasi iniziali dell’infezione (generalmente entro la prima settimana) e permangono nell’organismo per un breve lasso di tempo. Le IgG vengono invece prodotte circa 10-12 giorni dopo l’inizio dell’infezione, ma restano in circolazione più a lungo (periodo di tempo variabile a seconda del patogeno in questione). Per un certo periodo di tempo sia le IgG che le IgM possono essere presenti nel siero di un individuo.

La presenza di IgM denota che l’infezione è ancora in corso o molto recente, mentre la presenza delle sole IgG indica un’infezione pregressa.

Tra i test sierologici possiamo distinguere quelli quantitativi, capaci di determinare la concentrazione degli anticorpi di interesse, e quelli qualitativi che invece hanno come risultato solo la presenza o assenza degli anticorpi.

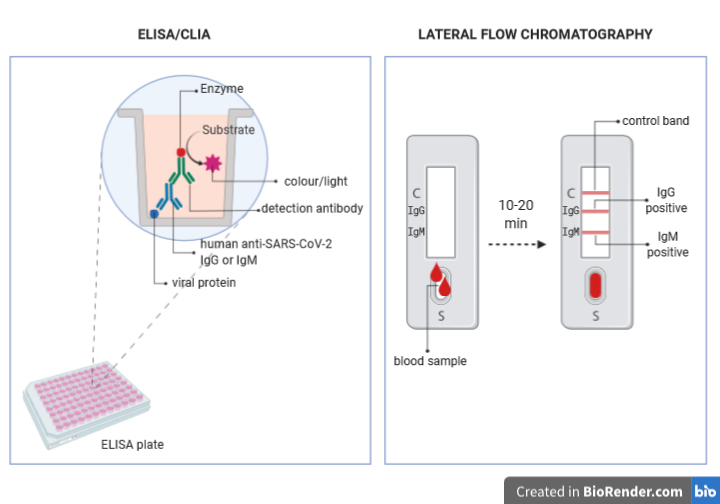

I test che vengono svolti negli ospedali e nei laboratori autorizzati sono quantitativi e sono fondalmentalmente di due tipologie: ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay ) e CLIA (chemioluminescence assay).

Il principio alla base di queste tecniche è il seguente:

- su un supporto solido (il fondo dei pozzetti di una piastra) sono legate in maniera indissolubile le proteine del virus

- il siero da testare viene aggiunto nei pozzetti in diverse diluizioni; se nel siero sono presenti gli anticorpi essi si uniranno alle proteine virali

- un anticorpo capace di riconoscere le IgG o le IgM umane viene aggiunto al pozzetto (anticorpo di detezione); se gli anticorpi anti SARS-CoV-2 erano presenti nel siero del paziente, gli anticorpi di detezione si legheranno ad essi. Gli anticorpi di detezione sono stati modificati in modo da essere uniti (coniugati) ad un estremità a una molecola (enzima) capace di produrre colore (nel caso dell’ELISA) o luce (nel caso del CLIA) quando una molecola specifica (substrato) viene aggiunto al campione.

- Un apposito substrato viene aggiunto ai pozzetti e si misura l’intensità del colore o della luce prodotti dalla reazione con l’enzima coniugato all’anticorpo di detezione

- A partire dall’intensità di colore o di luce si calcola la concentrazione di anticorpi anti SARS-CoV-2 presenti nel siero del paziente.

I test rapidi di cui sentiamo parlare spesso in queste ultime settimane sono invece qualitatitivi e si basano su una tecnologia detta Lateral Flow Chromatography.

Il dispositivo per la realizzazione di questo test è una piccola striscia di una resina speciale, in cui sono posizionati in punti diversi degli anticorpi anti-IgM e degli anticorpi anti-IgG.

- Ad una estremità del dispositivo è presente un pozzetto in cui viene deposta una goccia di sangue che si vuole testare.

- La parte liquida del sangue (che contiene gli anticorpi) inizierà a muoversi per capillarità lungo la striscia di resina, e incontrerà in una porzione di essa (la camera di coniugazione) delle proteine del virus coniugate a delle particelle d’oro colloidale che hanno un colore rosa-rossastro.

- Se nel sangue del paziente ci sono degli anticorpi contro le proteine virali si uniranno ad esse e le trascineranno con se mentre continuano a muoversi per capillarità lungo la striscia fino a quando non incontreranno gli anticorpi anti-IgG o anti-IgM legati al dispositivo.

- L’unione degli anti-anticorpi alle IgG o IgM unite alle proteine virali coniugate con le particelle d’oro colloidale determinerà la comparsa di una banda rossa nel punto in cui sono adesi gli anticorpi, rendendo facilmente visibile la loro presenza o assenza.

- L’intensità del colore della banda potrà indicarci se gli anticorpi sono tanti o pochi, ma non potremo calcolarne l’esatta concentrazione.

Questi dispositivi hanno anche un sistema di controllo, ovvero una terza banda in cui sono adesi anticorpi che riconoscono anticorpi non umani specifici per altre proteine. Gli anticorpi non umani e le proteine che essi riconoscono coniugate a particelle di oro colloidale si trovano nella camera di coniugazione del dispositivo e si muoveranno per capillarità lungo la resina insieme al campione, finché non incontreranno i loro anti-anticorpi. Solo se la banda di controllo diventerà rossa il test potrà essere considerato valido.

(Quelli appena descritti sono solo due esempi delle tante tecniche in cui gli anticorpi vengono usati come strumenti in laboratorio.)

Immagini create su BioRender.com

Bibliografia:

Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. 5th edition.The distribution and functions of immunoglobulin isotypes, Janeway C.A. Jr et al., New York: Garland Science 2001https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK27162/

Chemiluminescent immunoassay technology: what does it change in autoantibody detection?, Cinquanta L. et al., Autoimmun Highlights 2017 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13317-017-0097-2

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA): the basics,Shah K. et al., British Journal of Hospital Medicine 2016 https://doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2016.77.7.C98

Lateral Flow Technology for Field-Based Applications—Basics and Advanced Developments,O’Farrell B., Topics in Compan An Med 2015 https://doi.org/10.1053/j.tcam.2015.12.003