“Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2” by NIAID is licensed under CC BY 2.0 (Particelle virali che emergono dalla superficie di una cellula infettata)

“Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2” by NIAID is licensed under CC BY 2.0 (Particelle virali che emergono dalla superficie di una cellula infettata)

A dicembre del 2019 abbiamo iniziato a sentir parlare di un nuovo virus che si stava diffondendo in Cina causando un alto numero di casi di polmonite, chiamato temporaneamente 2019-nCoV.

L’11 febbraio 2020 il virus venne ufficialmente denominato SARS-CoV-2 dal Comitato Internazionale per la Tassonomia dei Virus (International Commitee on Taxonomy of Viruses – ICTV), e l’Organizzazione Mondiale della Sanità (OMS) stabilì il nome della malattia da esso causata: COVID-19. Le manifestazioni cliniche dell’infezione sono eterogenee, includendo portatori asintomatici, sindrome respiratoria acuta e polmonite.

L’11 marzo 2020 l’OMS dichiarò che, avendo superato 118.000 casi in 114 Paesi, COVID-19 poteva essere definito come una pandemia.

Dal momento in cui venne riportato il primo caso di polmonite atipica a Wuhan al 22 marzo 2020 sono state prodotte 494 pubblicazioni scientifiche riguardanti le caratteristiche cliniche dei pazienti, le vie di trasmissione del virus, la resistenza sulle superfici e nell’aria, la caratterizzazione molecolare, modelli matematici di diffusione, patogenesi, possibili trattamenti e vaccini.

Qui di seguito riporto le informazioni essenziali che ho trovato in una frazione degli articoli finora pubblicati.

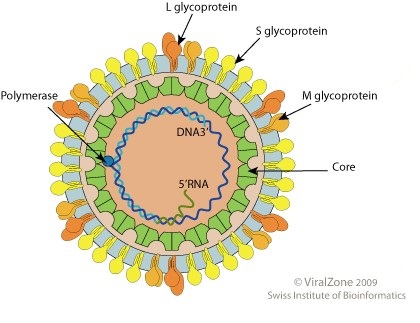

Origine del virus. SARS-CoV-2 è il settimo tra i coronavirus che possono infettare l’uomo finora conosciuti. La proteina Spike (S) di SARS-CoV-2, così come quella di SARS-CoV, riconosce la proteina umana ACE-2 e proteine simili presenti in altri animali. Il sito di legame tra la proteina S del nuovo virus e la ACE-2 umana è però diverso e meno efficiente di quello già noto del virus SARS-CoV, indicando che il virus non è stato creato appositamente in laboratorio, ma è frutto di mutazioni casuali naturali.

Il virus che sta circolando attualmente nella popolazione potrebbe essersi evoluto in due modi:

1) selezione naturale in un animale (probabilmente presente nel mercato di Wuhan) prima del salto di specie

2) selezione naturale negli umani dopo il salto di specie.

Seguendo la prima ipotesi, l’analisi del genoma di SARS-CoV-2 ha rivelato molte somiglianze con un virus simile che infetta i pipistrelli, e uno che infetta il pangolino. Nonostante ciò nessuno tra i coronavirus isolati finora da questi animali ha una percentuale di similarità tale da poter essere il diretto progenitore del virus umano, ma bisogna tener presente che non tutti i virus che infettano questi animali sono conosciuti o caratterizzati. Bisognerebbe trovare una specie di pipistrello o pangolino con una ACE-2 molto simile a quella umana, in cui SARS-CoV-2 possa aver acquisito le sue caratteristiche prima di passare all’uomo.

La seconda ipotesi è che il virus sia stato trasmesso da un animale all’uomo e poi da uomo a uomo passando inizialmente inosservato, e che durante questi passaggi abbia acquisito delle mutazioni che hanno migliorato la capacità della proteina S di unirsi alla ACE-2 umana. La similarità tra la proteina S del virus del pangolino e quella del virus umano fa pensare che sia questo l’animale in cui il virus si sia originato, per poi acquisire nell’uomo delle caratteristiche più vantaggiose. Sono necessari ulteriori studi per stabilire quale delle due ipotesi sia la corretta.

Il fatto che SARS-CoV-2 presenti sequenze simili ad altri virus conosciuti, sia altri coronavirus che virus diversi come HIV, non significa che il virus sia stato creato in laboratorio bensì è indicativo della sua naturale evoluzione: così come ci sono sequenze simili tra i geni umani e i geni di altri animali, allo stesso modo esistono sequenze simili tra i geni di virus diversi, questo perché l’evoluzione ha fatto sì che sequenze simili venissero selezionate per svolgere funzioni simili in organismi diversi. Inoltre, se il virus fosse stato creato in laboratorio, le sequenze “prese” da altri virus già conosciuti sarebbero esattamente identiche (“copiate e incollate”) e non semplicemente simili.

Trasmissione e periodo di incubazione. La proteina ACE-2 a cui il virus è capace di legarsi, è presente su molti tessuti dell’organismo umano, e in particolar modo nelle mucose del cavo orale, ritenuto la principale via di ingresso del virus. È molto probabile che anche le congiuntive siano una via di entrata per il virus nel nostro organismo, dato che sono stati riportati casi in cui medici che indossavano una mascherina per proteggere la bocca e il naso, ma non degli occhiali di protezione, sono stati contagiati da pazienti postivi al virus.

Trattandosi di un virus che interessa le vie respiratorie, la presenza del virus viene ricercata nei tamponi orofaringei e nasali, nell’espettorato, nel fluido di lavaggio bronco alveolare, e nelle biopsie dei pazienti più gravi. Uno studio ha analizzato diversi tipi di campioni prelevati da 205 pazienti ricoverati in 3 ospedali cinesi, ed in alcuni casi il virus è stato trovato anche nel sangue (1%) e nelle feci (29% dei casi). La presenza di virus vitale in questo tipo di campioni suggerisce che l’infezione in alcuni casi può essere sistemica (cioè non limitata alle sole vie respiratorie) e che il virus potrebbe essere trasmesso anche per via oro-fecale.

Diversi studi hanno calcolato il periodo di incubazione, ovvero il lasso di tempo tra l’esposizione all’agente infettivo e la comparsa dei sintomi, ottenendo risultati variabili: il periodo di incubazione sembra essere di circa 5 giorni, ma con valori che variano da 2 a 14 giorni (motivo per cui si raccomanda una quarantena di 14 giorni se si hanno avuto contatti con individui positivi). Sarà necessario studiare un numero più elevato di casi per determinarlo con esattezza.

Un altro aspetto importante è il periodo di latenza, cioè l’intervallo di tempo tra l’esposizione al virus e il momento in cui si diventa contagiosi: l’analisi di dati su pazienti asintomatici o con sintomi lievi risultati positivi al SARS-CoV-2, suggerisce che esso sia più breve del periodo di incubazione, ovvero che si possa essere contagiosi prima di aver manifestato i sintomi.

Resistenza sulle superfici. È stato dimostrato che SARS-CoV-2 può resistere stabilmente nell’aria per 3 ore. Per quanto riguarda le superfici, esso può resistere in forma vitale (cioè capace di infettare) fino a 72 ore sulla plastica, 48 ore sull’acciaio inossidabile, 8 ore sul cartone e 4 ore sul rame. Questi dati implicano che il virus si trasmette tramite aerosol e tramite contatto con oggetti contaminati. Gli oggetti possono essere decontaminati usando reagenti che si sono dimostrati efficaci per altri coronavirus, contenenti una di queste tre sostanze alla giusta concentrazione: alcol etilico tra il 62 e il 71%, acqua ossigenata allo 0.5% o ipoclorito di sodio allo 0.1%.

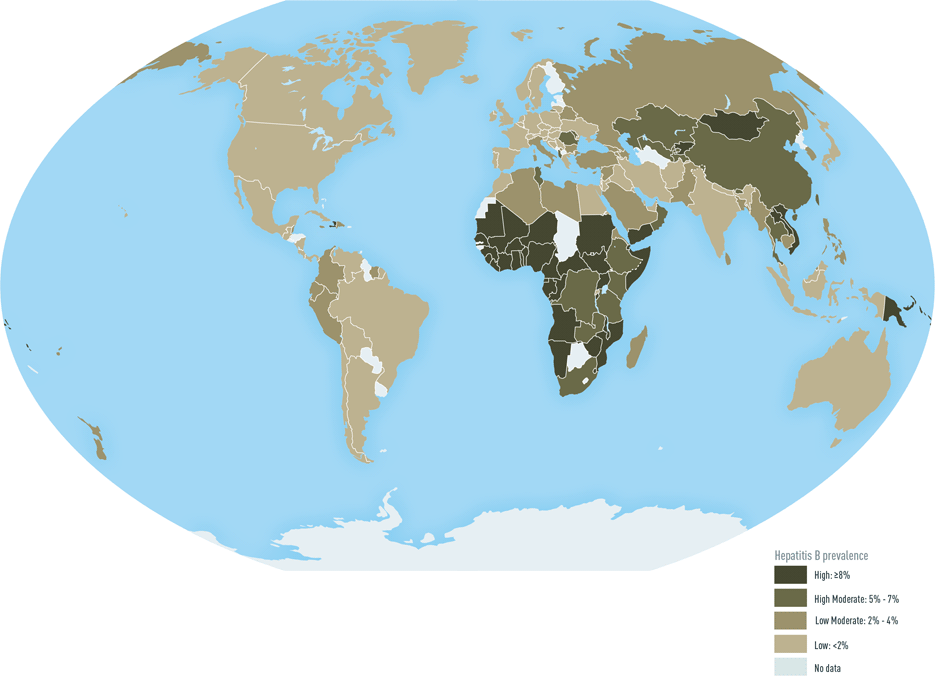

Sviluppo di un vaccino. Al momento non è chiaro se l’infezione da SARS-CoV-2 induca la produzione di anticorpi, se questi siano protettivi verso una seconda infezione, e per quanto tempo restino nell’organismo. Diversi centri di ricerca e compagnie farmaceutiche stanno lavorando per trovare un vaccino efficace contro SARS-CoV-2. Per lo sviluppo di un vaccino è necessario innanzitutto individuare quali proteine del virus siano capaci di indurre la produzione di anticorpi (antigeni). Affinché un vaccino sia efficace tali anticorpi devono essere capaci di “intercettare” del virus; nel caso di alcune infezioni virali, infatti, gli anticorpi prodotti dal sistema immunitario non bloccano il virus, come nel caso degli anticorpi che riconoscono l’antigene e del virus dell’epatite B (di cui ho parlato in un precedente articolo). Una volta individuato l’antigene virale con le caratteristiche necessarie, bisogna studiare la composizione del vaccino e testarne in primo luogo la sicurezza (assenza di effetti collaterali) ed in seguito l’efficacia, prima su modelli animali e poi sull’uomo.

La proteina su cui si stanno concentrando gli studi è la proteina S, esposta sulla superficie del virus e responsabile del legame con le cellule umane. Il 16 marzo 2020 la compagnia farmaceutica statunitense Moderna ha iniziato il primo test clinico per valutare la sicurezza di un potenziale vaccino per SARS-CoV-2; la compagnia prevede che se il suo vaccino dovesse risultare sicuro ed efficace, potrebbe essere disponibile sul mercato tra 12-18 mesi.

Questi sono solo alcuni degli aspetti del virus e della malattia che gli scienziati di tutto il mondo stano studiando. Se c’è qualche altra cosa che vorreste sapere su SARS-CoV-2 o su COVID-19 lasciate un commento e cercherò per voi la risposta.

BIBLIOGRAFIA:

https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen

The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2, Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, Nature microbiology 2020 http://doi.org/10.0.4.14/s41564-020-0695-z

The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2, Andersen K.G et al., Nature 2020 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9

No credible evidence supporting claims of the laboratory engineering of SARS-CoV-2, Shan-Lu L. et al., Emerging microbes and infections 2020 http://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1733440

Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis, Hamming I. et al, Journal of Pathology 2004 http://doi.org/10.1002/path.1570

High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa, Xu H. et al., International journal of oral science 2020 http://doi.org/10.1038/s41368-020-0074-x

2019-nCoV transmission through the ocular surface must not be ignored, Cheng-wei Lu et al., The Lancet 2020 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30313-5

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Different Types of Clinical Specimens, Wang W. at al., Journal of the American Medical Association, 2020 http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3786

Asymptomatic carrier state, acute respiratory disease, and pneumonia due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): Facts and myths, Lai C-C et al., Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and infection 2020 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2020.02.012

The Incubation Period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) From Publicly Reported Confirmed Cases: Estimation and Application, Lauer S.A. et al., Annals of Internal Medicine 2020 http://doi.org/10.7326/M20-0504

Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1, van Doremalen N. et al., The New Egland Journal of Medicine 2020 http://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2004973

Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents, Kampf G. et al., Journal of Hospital Infection 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.022

Coronavirus vaccines: five key questions as trials begin, Callaway E., https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00798-8

https://www.modernatx.com/modernas-work-potential-vaccine-against-covid-19

A Sequence Homology and Bioinformatic Approach Can Predict Candidate Targets for Immune Responses to SARS-CoV-2, Grifoni A. at al., Cell Host & Microbe 2020 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2020.03.002

Development of epitope‐based peptide vaccine against novel coronavirus 2019 (SARS‐COV‐2): Immunoinformatics approach, Bhattacharya M. et al., Journal of Medical Virology 2020 http://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25736