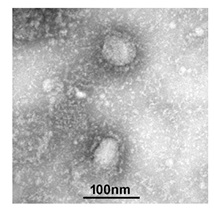

Nelle ultime settimane è stato identificato un nuovo virus che causa polmonite negli esseri umani: è stato chiamato 2019-nCoV (2019 novel Coronavirus) e si è originato nella città cinese di Wuhan.

Il sito del Centro Europeo per la Prevenzione e il controllo delle Malattie (ECDC) riporta che al 26 gennaio 2020 sono stati confermati 2026 casi di contagio, di cui 1988 in Cina. Gli altri paesi coinvolti sono Taiwan, Tailandia, Australia, Malesia, Singapore, Francia, Giappone, USA, Corea del Sud, Vietnam, Canada e Nepal. Tutte le persone contagiate dal virus tranne un unico in caso in Vietnam, erano state recentemente in Cina. Tra i pazienti colpiti alcuni hanno sviluppato una patologia grave che è risultata letale in 56 casi (tutti registrati in Cina), mentre altri hanno manifestato sintomi più lievi che non hanno richiesto un ricovero prolungato in ospedale. I sintomi dell’infezione da 2019-nCoV sono febbre, tosse, dolori muscolari e debolezza.

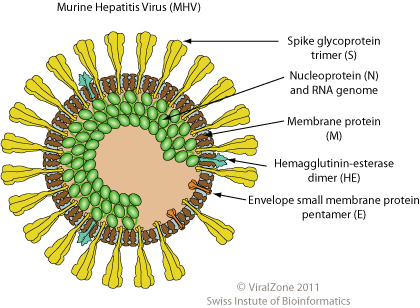

2019-nCoV fa parte della famiglia dei Coronaviridae, caratterizzati da un genoma a RNA contenente 6 o più geni, e dotati di pericapside (involucro lipidico in cui sono inserite anche proteine del virus). I coronavirus infettano mammiferi e uccelli e si trasmettono tra animali della stessa specie, ma talvolta possono trasmettersi dagli animali all’uomo, come nel caso del coronavirus che causò la pandemia di SARS* nel 2002 (trasmesso dagli zibetti) e di quello che causò la MERS** nel 2012 (trasmesso dai dromedari). I coronavirus capaci di infettare le persone causano malattie respiratorie che vanno dal comune raffreddore a patologie più gravi come la MERS.

I geni dei coronavirus contengono le istruzioni per la produzione delle proteine virali, le più importanti delle quali si chiamano Spike (S), Membrane (M), Envelope (E), e Nucleocapsid (N).

La proteina Spike sporge dall’involucro esterno formando la “corona” visibile al microscopio che dà il nome a questa famiglia di virus; ha la funzione di consentire l’adesione tra il virus e le proteine che si trovano sulla superficie esterna delle cellule dell’organismo che verrà infettato. In alcuni casi la proteina S ha anche la funzione di far fondere le cellule infettate con altre cellule vicine per favorire la diffusione del virus.

La proteina M attraversa la membrana del virus facendola curvare e determinando la forma sferica del virione. M interagisce anche con il nucleocapside costituto dall’RNA del virus e dalla proteina N.

La proteina E è invece necessaria per l’assemblaggio di nuove particelle virali e per il loro rilascio dalla cellula infettata, è quindi necessaria per la diffusione del virus.

Il nuovo virus 2019-nCoV ha iniziato a diffondersi da un mercato della città di Wuhan, in cui vengono commerciati animali vivi a scopo alimentare, suggerendo il contagio da animale a uomo. Col passare del tempo però sono stati registrati casi di persone infettate dal virus che non avevano frequentato il mercato di Wuhan, dimostrando che il virus è diventato capace di trasmettersi da persona a persona. Molto probabilmente il contagio avviene per via aerea attraverso piccole goccioline espulse con la tosse o con gli starnuti. Gli scienziati stanno lavorando per capire con quanta facilità il virus si possa diffondere tramite questa modalità da persona a persona, e quale sia la sua virulenza, ovvero la capacità di causare una malattia e con quale severità. Al momento sembra che affinché avvenga il contagio sia necessario essere a stretto contatto con un individuo infetto.

L’ipotesi avanzata in un primo momento secondo cui i serpenti sarebbero stati la fonte di questo virus è stata successivamente smentita, e ancora non si sa esattamente come si sia originato. La sequenza del suo RNA è molto simile sia a quella di altri virus che circolano tra i pipistrelli sia a quello della SARS, e sono in corso degli studi per capire quale sia la specie che l’abbia inizialmente trasmesso all’uomo.

Al momento non esiste un vaccino per proteggerci da questo virus né un trattamento specifico, ma i sintomi della malattia causata da 2019-nCoV possono essere curati.

Restano valide le precauzioni che vengono messe in atto con altri virus respiratori: coprirsi la bocca quando si starnutisce, usare fazzoletti usa e getta, lavarsi spesso le mani con acqua e sapone o con altri prodotti disinfettanti, non toccarsi gli occhi, la bocca o il naso senza aver prima lavato le mani.

Ma come nasce un nuovo virus? E come è possibile che si trasmetta tra specie diverse passando da un animale all’uomo?

I virus emergenti capaci di infettare l’uomo hanno prevalentemente genomi fatti di RNA, e si originano con più frequenza in regioni densamente popolate e in cui l’attività umana è particolarmente intensa.

Affinché un nuovo virus possa emergere, devono verificarsi diversi fattori tra cui lo stretto contatto tra animali e l’uomo, e delle modificazioni genetiche del virus.

Questo processo avviene attraverso tre fasi:

1) il virus acquisisce la capacità di infettare cellule di un nuovo organismo,

2) il virus si adatta al nuovo ospite e viene trasmesso tra individui,

3) il nuovo virus acquisisce la capacità di diffondersi in forma epidemica nella popolazione.

Mentre le prime due fasi richiedono cambiamenti genetici nel virus, la terza fase coinvolge cambiamenti nelle dinamiche della popolazione infettata come l’aumento dei contatti tra individui e i loro spostamenti.

Quando diciamo che un virus replica, intendiamo che produce molte copie del suo materiale genetico; i virus però non hanno modo di controllare la fedeltà delle copie che producono, e quindi spesso introducono degli errori nel loro genoma (mutazioni). Questo porta alla formazione di particelle virali con genoma simili ma non esattamente identici a causa della presenza di errori di “copiatura”.

Se uno di questi errori cambia le istruzioni per la produzione della proteina che si lega alle cellule da infettare, e la nuova versione della proteina è capace di legarsi a cellule di un organismo diverso, ecco che avviene il “salto di specie”.

Il genoma di un virus può modificarsi anche tramite altri due fenomeni chiamati “ricombinazione” e “riarrassortimento”.

La ricombinazione avviene quando frammenti di genomi di virus simili tra loro si mescolano formando nuove sequenze. È quello che è successo nel caso di un coronavirus responsabile della bronchite nelle galline: una ricombinazione nella sequenza della proteina Spike con un altro gene S di origine sconosciuta ha dato vita a un virus ibrido che è risultato capace di infettare i tacchini causando però una malattia intestinale invece che respiratoria. Questo nuovo virus inoltre perse la capacità di infettare le galline.

Il riassortimento avviene invece solo in quei virus il cui genoma è costituito da più frammenti di RNA o DNA (virus segmentati). Se una cellula viene infettata contemporaneamente da due virus segmentati diversi tra loro, può accadere che frammenti di provenienza diversa vengano impacchettati nella stessa particella virale, producendo dei virus che sono una combinazione dei due virus originali.

Anche il riassortimento può facilitare il salto di specie. È quello che è successo con il virus pandemico 2009 IAV H1N1: si ritiene che nel 1998 frammenti provenienti dai virus dell’influenza aviaria, suina e umana si siano combinati in un nuovo virus capace di circolare tra i suini, chiamato H3N2 IAV; nel 2009 questo virus si è a sua volta riassortito con un altro virus dell’influenza dei polli formando un terzo virus capace di diffondersi tra la popolazione umana.

Da quanto abbiamo detto finora risulta chiaro che I virus hanno una grande capacità di evolversi rapidamente, e ciò li rende particolarmente pericolosi perché così facendo possono sfuggire alla risposta immunitaria e ai trattamenti antivirali. Bisogna però sottolineare che solo una piccola percentuale dei nuovi virus che si formano riescono ad incontrare facilmente una nuova specie ospite e ad adattarsi ad essa. Infatti numero di particelle virali che vengono trasmesse da individuo a individuo dipende dalla capacità del virus di crescere all’interno dell’organismo infettato, e questo è un punto critico per molti virus emergenti.

Quando compare un nuovo virus possono verificarsi diverse situazioni:

a) se il virus si replica con poca efficienza nel nuovo ospite ci saranno meno particelle virali liberate (per esempio con le goccioline emesse con uno starnuto) quindi meno particelle che raggiungeranno un altro individuo da infettare;

b) se il virus è troppo aggressivo non permetterà all’ospite di sopravvivere abbastanza per trasmettere un numero elevato di particelle virali ad altri individui e la sua diffusione sarà limitata (la morte dell’ospite è uno svantaggio per il virus);

c) solo quei virus che riusciranno ad adattarsi rapidamente al loro ospite e a raggiungere il giusto equilibrio con esso saranno capaci di crescere e diffondersi efficacemente nella popolazione.

Nel mondo attuale l’emergere di nuove malattie infettive e il riemergere di altre è facilitato dalla globalizzazione che consente il rapido movimento di persone tra luoghi del pianeta anche molto lontani tra loro. I viaggiatori possono portare con sé da un posto all’altro nuovi virus favorendone la diffusione. Anche gli insetti vettori di virus possono essere trasportati in questo modo, introducendo patogeni in nuove aree. Il cambiamento climatico può avere degli effetti in questo contesto, in quanto il verificarsi di condizioni climatiche favorevoli alla sopravvivenza e alla riproduzione dei vettori in zone diverse da quella d’origine può amplificare la diffusione dei virus da essi trasportati.

Il vantaggio che la globalizzazione ci offre per rispondere a queste situazioni è la rapida comunicazione e collaborazione tra scienziati a livello internazionale, come ci sta dimostrando il caso del 2019-nCoV: pochi giorni dopo i primi casi di contagio il virus è stato identificato e sequenziato, la sequenza è stata resa pubblica consentendo a diversi gruppi di ricercatori di iniziare a lavorare per individuarne l’origine, realizzare dei test diagnostici ed elaborare modelli matematici per prevederne la velocità di diffusione.

In questo momento ricercatori di tutto il mondo sono al lavoro per capire meglio il meccanismo con cui 2019-nCoV causa la malattia e per riuscire a limitarne la diffusione.

*SARS Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome; ** MERS Middle East Respiratory Syndrome

Per saperne di più sulle caratteristiche generali dei virus, leggi il mio post Il magico mondo dei virus.

Bibliografia

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical-distribution-2019-ncov-cases

World Health Organization: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019; https://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ ; https://www.who.int/csr/sars/en/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/summary.html

Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Huang C. et al, Lancet 2020, http://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30183-5

Coronaviruses: genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. Chen Y. et al., J Med Virol 2020, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0

Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Schoeman D., Fielding B.C., Virol J 2019, http://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0

Evolutionary ecology of virus emergence. Dennehy J.J., Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci 2017, http://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13304

Emerging and re-emerging viruses in the era of globalisation. Zappa A. et al., Blood Transfus. 2009, http://doi.org/10.2450/2009.0076-08

Foto da http://www.im.cas.cn/xwzx2018/jqyw/202001/t20200124_5494401.html