Nel Regno Unito sono stati approvati tre vaccini per contrastare la pandemia: si tratta di due vaccini a mRNA e un vaccino basato su un vettore virale. Quest’ultimo, chiamato AZD1222 è stato sviluppato dall’Università di Oxford e dall’industria biofarmaceutica AstraZeneca.

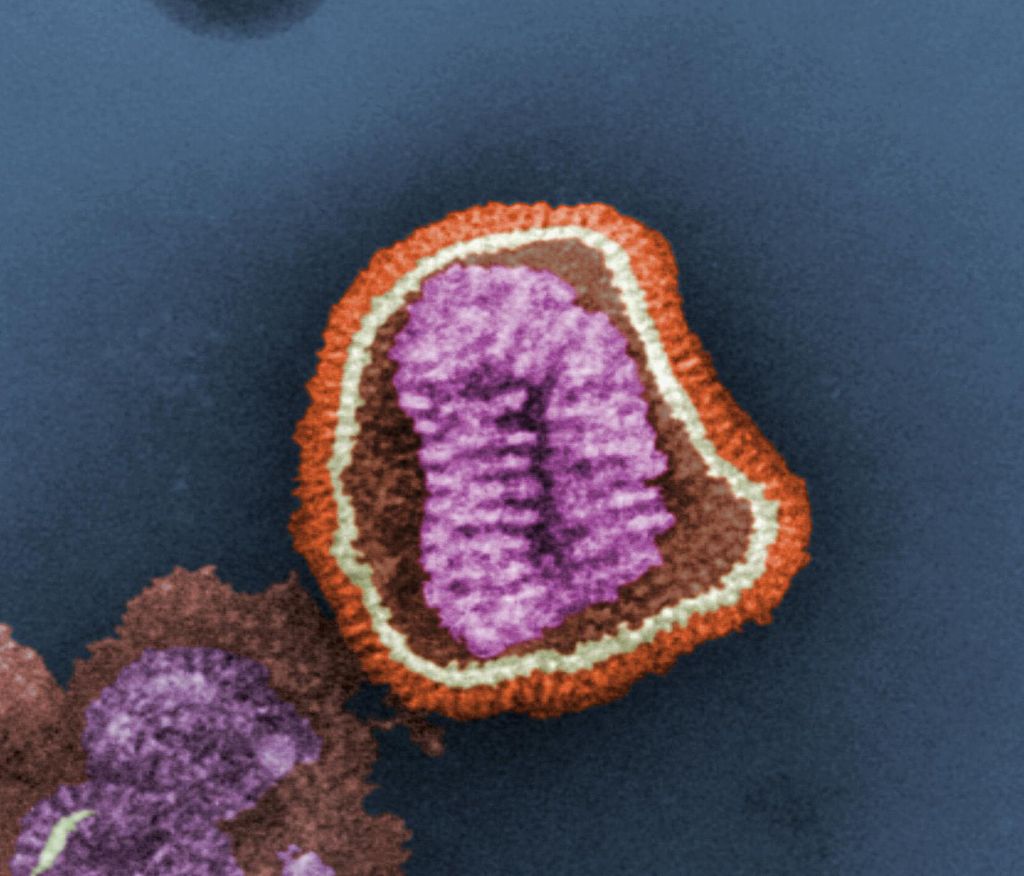

AZD1222 è basato su un Adenovirus degli scimpanzé, modificato in modo da non potersi replicare dentro le cellule infettate, e che porta al suo interno la sequenza di DNA necessaria per la produzione della proteina Spike di SARS-CoV-2.

È il primo vaccino di questo tipo ad essere approvato, ma la tecnologia era già disponibile e studiata per altri vaccini a partire dai primi anni Duemila.

Inizialmente i vettori basati su Adenovirus vennero sviluppati per essere usati in terapia genica, ovvero per trasferire une versione corretta dei geni mutati nelle cellule di pazienti affetti da malattie genetiche. Ben presto ci si rese conto però che questo tipo di trattamento induceva in molti casi una risposta immunitaria contro il vettore stesso: ciò che costituiva uno svantaggio come vettore per la terapia genica, rendeva gli Adenovirus degli ottimi candidati per essere usati come vaccini. Inoltre gli Adenovirus hanno il vantaggio di causare malattie con sintomi molto lievi (ad esempio il comune “raffreddore” è causato da un Adenovirus), possono infettare diversi tipi di cellule, e sono relativamente stabili, rendendone agevole l’uso clinico.

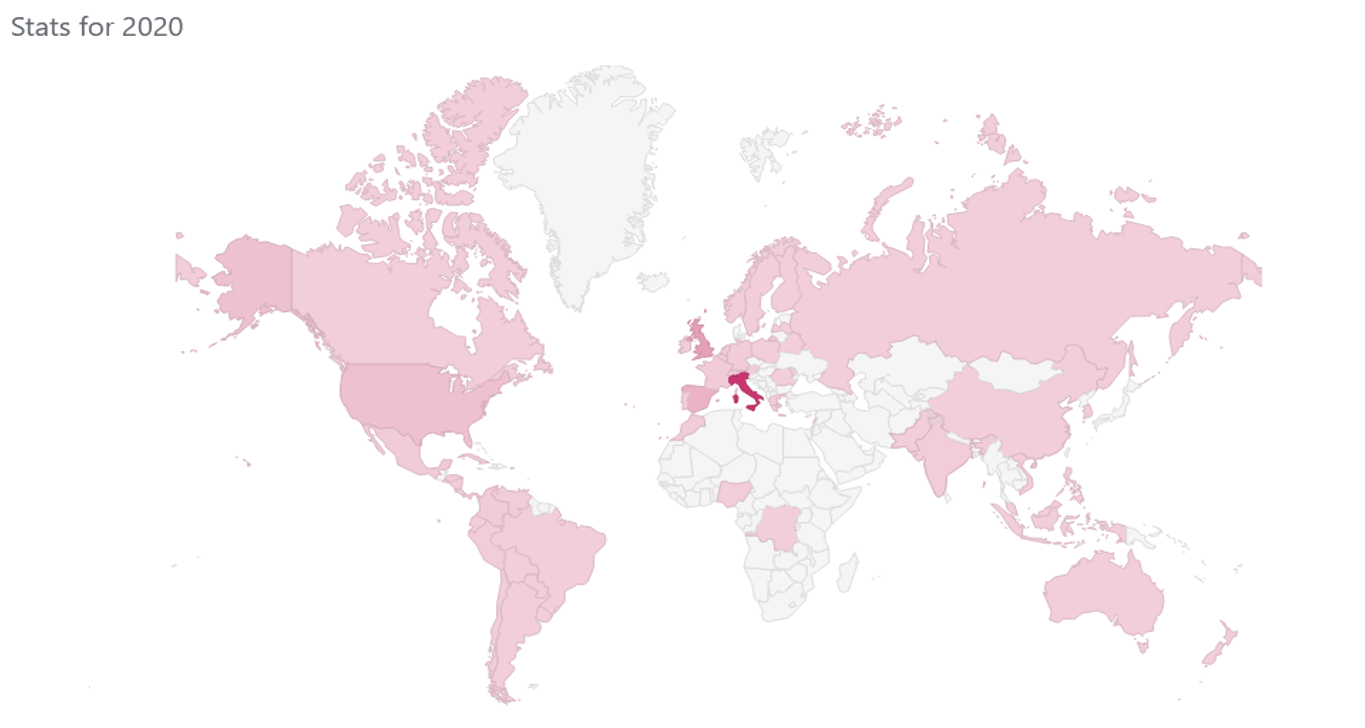

Gli adenovirus che infettano l’uomo possono causare sia infezioni acute con la presenza di sintomi, che infezioni persistenti nel tempo ma asintomatiche. Alcuni adenovirus sono molto comuni e infettano l’uomo durante l’infanzia. L’abbondanza di adenovirus umani e la frequenza delle infezioni, fa sì che molti di noi (tra il 45% e l’80% della popolazione a seconda dell’area geografica) abbiano un arsenale di anticorpi capaci di riconoscere e neutralizzare gli adenovirus. Per questo motivo per lo sviluppo di vaccini vengono usati o gli Adenovirus umani meno comuni (che infettano il 5-15% della popolazione mondiale) o quelli che infettano altre specie, come gli Adenovirus di scimpanzé.

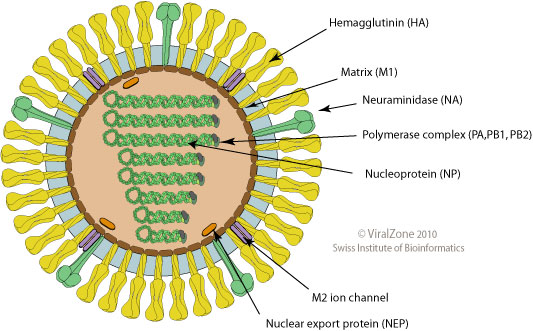

Gli adenovirus usati come vettori virali vengono modificati geneticamente in modo da:

- Eliminare i geni che possono causare la malattia

- Rendere il virus incapace di replicarsi dentro le cellule

- Rendere il virus incapace di provocare la morte delle cellule

- Eliminare i geni del virus che normalmente hanno il compito di frenare la risposta antivirale

- Produrre una proteina del patogeno contro cui si vogliono produrre anticorpi

È importante a questo punto capire che il vaccino non è fatto con un virus di scimpanzé, ma con un vettore geneticamente modificato (virus ricombinante) che mantiene solo le caratteristiche per noi vantaggiose del virus naturale, mentre quelle potenzialmente pericolose o che potrebbero rappresentare uno svantaggio sono state eliminate definitivamente.

Inoltre, il DNA di questi vettori non ha la capacità di integrarsi nel DNA umano, e non può interferire con l’attività di geni umani.

Dopo la vaccinazione, il virus ricombinante entra nelle cellule del sito dell’iniezione e rilascia il suo DNA nel nucleo della cellula. Qui il DNA viene trascritto in RNA, l’RNA lascia il nucleo e viene tradotto per produrre la proteina Spike di SARS-CoV-2. Come tutte le proteine prodotte durante un’infezione virale, anche Spike verrà “digerita” in tanti pezzettini, alcuni dei quali saranno esposti sulla superficie della cellula. Le cellule del sistema immunitario che pattugliano il tessuto vedranno le porzioni di Spike e la riconosceranno come “non umana”. Contemporaneamente, alcune delle particelle virali usate come vaccino, verranno catturate da altri tipi di cellule del sistema immunitario, e portate ai linfonodi. Questi eventi daranno il via alla risposta immunitaria che culminerà, tra le altre cose, con la produzione di anticorpi specifici contro Spike che saranno pronti per attaccare il vero SARS-CoV-2 in caso di infezione.

La vaccinazione con AZD1222 prevede due dosi, con un intervallo tra 4 e 12 settimane. I test clinici hanno dimostrato che:

- La seconda dose causa meno effetti secondari rispetto alla prima (meno dolore e gonfiore nel sito dell’iniezione, e meno pazienti hanno riportato febbre, mal di testa, malessere o dolori muscolari)

- L’intensità degli eventuali effetti collaterali non ha nessuna correlazione con l’efficacia della vaccinazione

- Dopo la prima dose l’organismo produce una certa quantità di anticorpi contro il vettore virale, ma essi non riducono l’efficienza della seconda dose, e non aumentano dopo il richiamo

- La vaccinazione induce una quantità di anticorpi anti-Spike superiore a quella osservata in pazienti che sono guariti da COVID-19, misurata tra 28 e 91 giorni dopo la conferma dell’infezione tramite PCR

- La quantità di anticorpi prodotti aumenta dopo la seconda dose

- Gli anticorpi prodotti in seguito alla vaccinazione sono in grado di compiere diverse funzioni nell’ambito della risposta immunitaria (attivazione della fagocitosi, attivazione del complemento e attivazione delle cellule Natural Killer)

- La vaccinazione induce anche una risposta immunitaria mediata dai linfociti T, importante per la risoluzione dell’infezione naturale (una buona risposta cellulare è stata osservata in pazienti con sintomi lievi e guarigione più rapida)

- L’efficacia della vaccinazione è del 70.4%: tra i 131 casi di infezione sintomatica che si sono verificati su 11.636 partecipanti che hanno ricevuto la seconda dose, 30 sono stati registrati tra quelli che avevano ricevuto il vaccino (5.807) e 101 tra quelli del gruppo controllo (5.829)

- L’efficacia resta la stessa se la seconda dose viene somministrata 4, 6, 8 o 12 settimane dopo la prima dose.

Basandosi su quest’ultimo dato, il governo del Regno Unito ha deciso di usare tutte le dosi al momento disponibili per garantire una prima dose al numero più alto di persone possibile, e di ritardare la somministrazione del richiamo fino a 12 settimane (quando altrettante dosi saranno disponibili); l’obiettivo di questa strategia sarebbe quello di permettere a quante più persone di iniziare a sviluppare una risposta immunitaria nel più breve tempo possibile, data la situazione di emergenza. La seconda dose verrà comunque garantita a tutti entro 12 settimane dalla prima dose.

Alcuni scienziati hanno anche suggerito la possibilità per il futuro di usare diversi tipi di vaccini tra quelli autorizzati per la prima dose e i successivi richiami, in quanto ognuno di essi attiva il sistema immunitario in modo leggermente diverso, e quindi una combinazione potrebbe indurre una risposta immunitaria più completa. Al momento però questa soluzione non è stata ancora adottata.

Immagine: Adenovirus, TEM, di David Gregory & Debbie Marshall, Licenza Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0), da https://wellcomecollection.org/works/d34rspdt

Bibliografia:

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/oxford-universityastrazeneca-covid-19-vaccine-approved

Replication-defective vector based on a chimpanzee adenovirus, Farina SF et al., Journal of Virology 2001 http://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.75.23.11603-11613.2001

Adenoviruses as Vaccine Vectors, Tatis N et al., Molecular Therapy 2004 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.07.013

Phase 1/2 trial of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 with a booster dose induces multifunctional antibody responses, Barrett JR et al., Nature Medicine 2020 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-01179-4

Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK, Voysey M et al., The Lancet 2020, http://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1