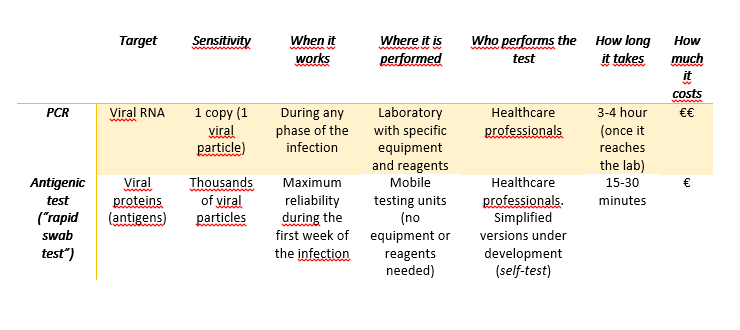

If one year ago someone had told me that our daily conversations would have had “virus, PCR, swab, antibodies” as keywords, I would have not believed it, but (unfortunately) these are trending topics in 2020.

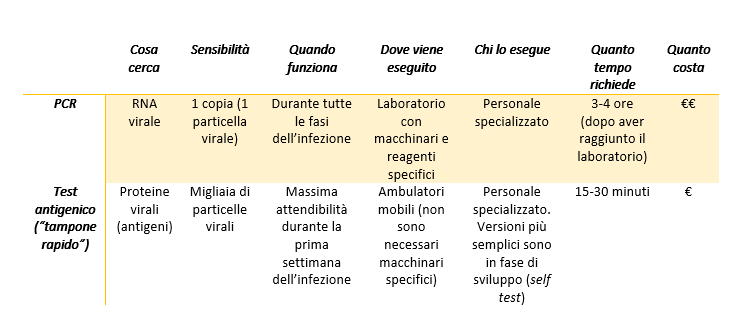

Since everybody talks about that, but many still mix things up, here are the differences between “swab test” and “rapid swab test” (as they are colloquially called).

The swab itself is just the stick used to collect a sample from the nasal or oro-pharyngeal cavities.

The difference stands in how the sample is analysed.

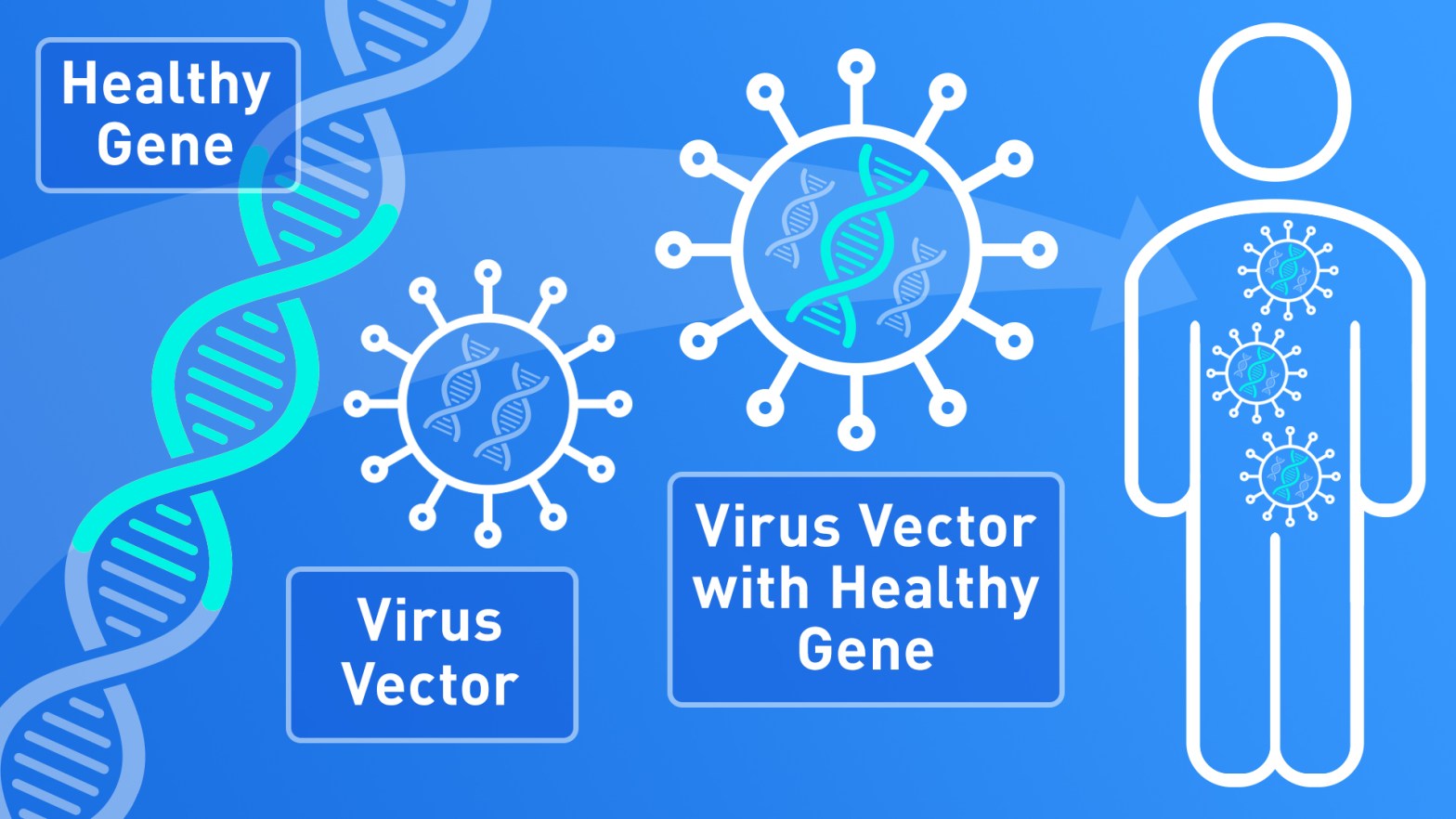

In the case of the swab tests we have heard since the beginning of the pandemics, the aim is to detect the genetic material of the virus.

- The viral RNA is extracted from the sample (don’t forget the genome of SARS-CoV-2 is made of RNA, not DNA)

- The RNA is “transformed” into DNA through a reaction called reverse transcription

- The DNA is in turn copied several times in a PCR (polymerase chain reaction), a technique able to detect even very small quantities of DNA.

- If the patients from which the sample has been collected does not have the virus, there is no DNA to copy, and the result of the PCR will be negative. On the other hand, if in the sample is present even only one copy of viral RNA, the reverse transcription and the PCR will be able to recognize and amplify it, and the result will be positive.

When the proteins of the virus (antigens) are the target of the tests, we talk about rapid swab tests (antigenic tests). The working principle is very similar to that of the serologic tests (see this post), but in this case, specific antibodies against the proteins of SARS-CoV-2 are immobilized on the device.

- The material collected with the swab is placed in a well at one extremity of the device

- The sample will flow by capillarity through the strip and it will go across the conjugation chamber, where it will encounter antibodies specific for the viral proteins conjugated to colloidal gold (pink-red coloured)

- If the sample contains viral antigens, they will bind the antibodies and will carry them while flowing in the strip until they encounter other antibodies against the same proteins, bound to the device

- The viral proteins will be trapped in a “sandwich” between the antibodies immobilized on the device and those conjugated to the colloidal gold particles, and this will determine the appearance of a red band, revealing the presence or absence

- The intensity of the band can indicate whether the amount of viral proteins in the sample is more or less abundant.

(The antigenic tests, similarly to the serologic ones, have an internal control to ensure the validity of the result).

While the PCR can detect very small amounts of genetic material, and therefore can be used in any phase of the infection, including on asymptomatic patients, the sensitivity of the antigenic tests is lower (the result is positive only if the sample contains a large amount of proteins). For this reason, the antigenic tests are used only on symptomatic patients to determine the cause of their symptoms, but they are not an official method for the screening of the virus: the results from antigenic tests need to be confirmed with a PCR, that is for the time being the only official diagnostic method.

Both the PCR and the antigenic tests must be done by healthcare professionals; there are no approved tests for the self-diagnosis, even if some companies are working on a simplified version of the rapid tests to be used at home, at school on at workplaces (the first data on the saliva-based antigenic test are not satisfactory).

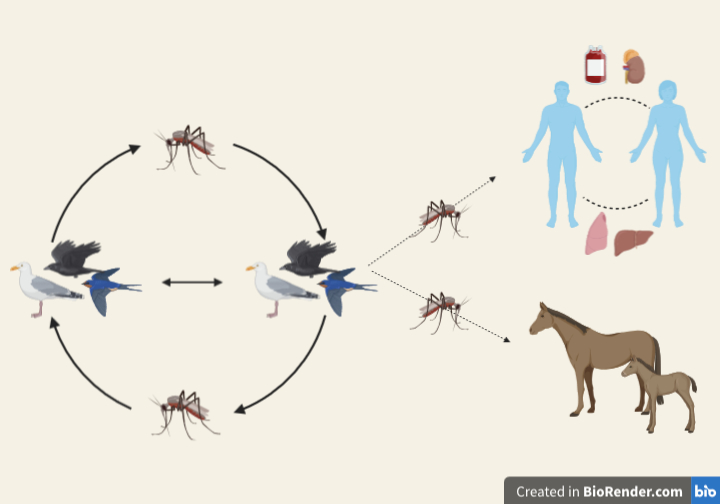

Image created in BioRender.com by Carla Usai

Bibliography

Fast Coronavirus tests are coming, Guglielmi G., Nature 2020 https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02661-2

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Overview-rapid-test-situation-for-COVID-19-diagnosis-EU-EEA.pdf

World Health Organization: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/antigen-detection-in-the-diagnosis-of-sars-cov-2infection-using-rapid-immunoassays